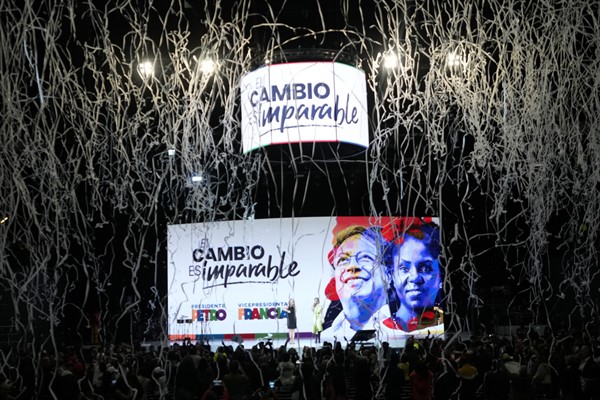

In 2022, it’s easy to be an opposition politician, party or political movement in Latin American democracies, where the political environment is about as anti-incumbent as it can get. Including the victory by Gustavo Petro in Colombia earlier this month, the parties of incumbent presidents have lost the past 14 consecutive democratic presidential elections in the region going back to 2018. Latin America has gone from a region where incumbent advantage was a major factor in elections to one where incumbent parties almost never win.

Of course, there is an obvious catch to this phenomenon: Once the opposition wins, it is no longer the opposition. As these newly elected figures take office, they face the same geopolitical headwinds that battered their predecessors. In many cases, the same domestic political gridlock that once helped them stymie their predecessors now works against them as incumbents. Meanwhile, the high expectations for change they created among their supporters can’t be met, leading to further disillusionment and anger at the political system.

Adding to the challenges facing the wave of left-wing presidents elected in the past two years is that they will have to govern on “hard mode.” And that’s the single biggest difference between them and the wave of presidents that governed in the 2000s, dubbed “the Pink Tide.”