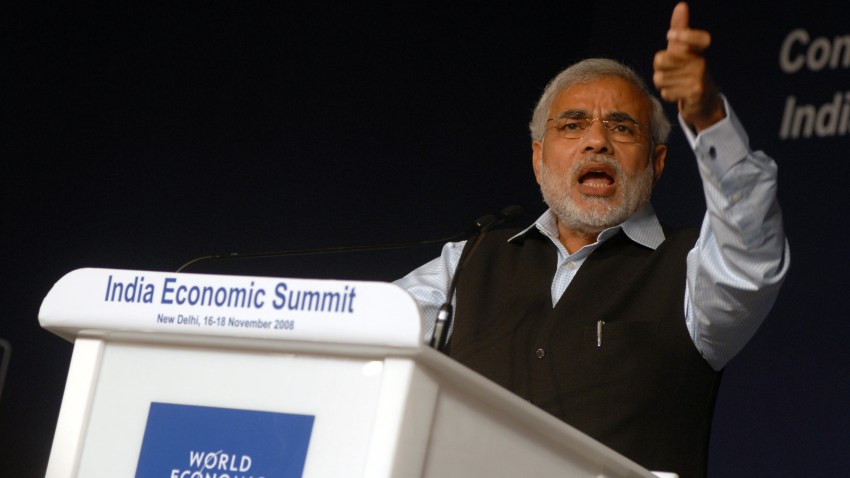

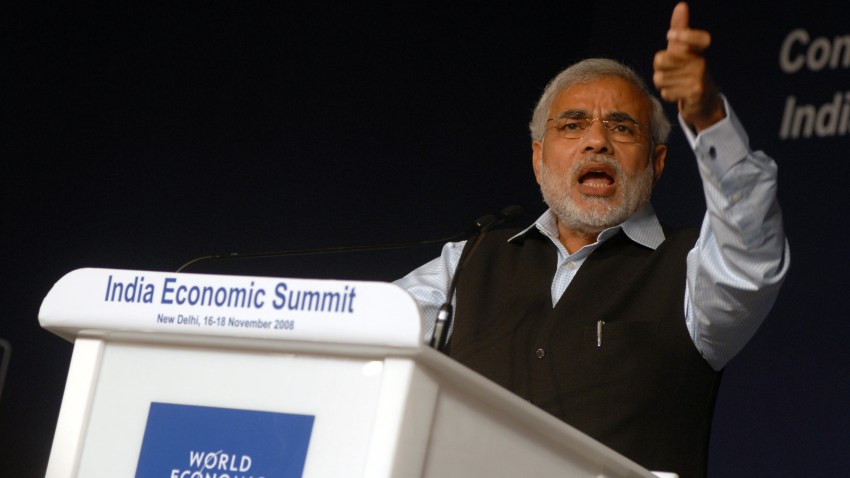

The Indian state of Gujarat has a mixed reputation in the United States. India watchers have praised its brisk economic growth and the ease of doing business there, but many also recall Gujarat’s spasm of communal violence in 2002 that left many hundreds dead. With India’s parliamentary elections a month away, the man who oversaw the state’s successes and failures as Gujarat’s chief minister since 2001, Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), looks likely to become India’s next prime minister.

This puts the United States in an awkward position. The State Department revoked Modi’s travel visa in 2005 for his apparent role in the 2002 violence. Faced with the prospect of a Modi victory in national elections, however, U.S. Ambassador to India Nancy Jo Powell met with Modi last month at his residence in Gujarat. But at the same time, the U.S. State Department maintained in a briefing last week that there had been no change in U.S. policy.

Sanjeev Shrivastav, a researcher at the Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses in New Delhi, wrote in an email to Trend Lines that the Indian reaction to this outreach has been positive. The outreach shows that the United States is “willing to maintain and continue strengthening its strategic partnership with India,” he says.

Indian defense analyst Rajeswari Rajagopalan of the Observer Research Foundation agrees that U.S. moves are seen in India as “pragmatic” and driven by a desire to avoid a downturn in the relationship. But economics are also a factor, and given Modi’s general support for foreign investment, the United States “does not want to lose out on opportunities should market liberalization pick up momentum” under a Modi government, he says.

The United States is seeking to re-energize a relationship that has progressed less quickly than many in Washington had hoped. Although India has emerged as the largest market for U.S. defense goods, ties between the two countries have been plagued by inertia as well as disagreements on issues ranging from Iran policy to climate change. And the recent spat

over the treatment of an Indian diplomat in New York highlighted the mistrust that still exists.

But as in previous Indian elections, relations with the United States aren’t at the top of the agenda for Indians. Milan Vaishnav of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace explained in a phone interview that the No. 1 issue in this election is instead India’s sluggish economy, with foreign affairs playing a relatively minor role. Modi has become “the man to beat” and has garnered broad support based in large part on Gujarat’s economic performance during his tenure as chief minister.

India’s incumbent prime minister, Manmohan Singh, has been in office for 10 years, Vaishnav adds, “and has been badly beaten up.”

Despite being singled out for U.S. disapproval, Modi appears to have adopted a moderate tone toward the United States. Vaishnav says that while Modi and his supporters have conveyed the message that the U.S. visa ban is arbitrary and unfair, Modi has not been personally vocal about the issue. And while he may have played “hard to get” in forcing the U.S. ambassador to come to him, he “didn’t come out with a big statement afterward,” says Vaishnav.

Rajagopalan predicts that Modi would be “keen to continue and further re-invigorate” relations with the United States. “Opportunities on the economic and defense front are likely to be pursued with greater vigor,” he says.

A dominant issue in the U.S.-India relationship over many decades has been the status of India’s nuclear weapons program. India’s decision to test a nuclear device in 1974 spurred efforts by the United States and others to deny India, which has never signed the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, access to nuclear technology. India, which tested again in 1998 and openly declared itself a nuclear weapons power, long bristled at a U.S.-led regime that some Indians labeled “nuclear apartheid.”

The 2008 U.S.-India nuclear deal—and related efforts to reduce export controls on India’s nuclear energy sector—relaxed some of the tensions associated with this issue, though without generating business for U.S. nuclear suppliers. Modi has supported India’s nuclear weapons tests, which were conducted by a previous BJP government, and has supported India’s “no first use” policy toward nuclear weapons. In Kumar’s view, under a Modi government “it is likely that India will continue with its existing nuclear policies.”

There is also the question of Modi’s approach to India’s two nuclear-armed neighbors, Pakistan and China. Rajagopalan points out that while the BJP is often seen as adopting a more “hard-line approach,” the previous BJP-led coalition “had done much more in terms of extending the olive branch.”

But while Modi will seek to avoid damaging these relationships if possible, he may be more “decisive” in his response to future high-level terrorist attacks like the 2008 attack on Mumbai, generally seen as originating from inside Pakistan. “The response may not be limited to political and diplomatic measures.”

As prime minister, Modi would likely continue to generate controversy in the United States. There are those in the U.S. who “don’t feel the need to move past 2002,” Vaishnav observes, and “who are vehemently opposed to Modi coming into this country.” But despite these concerns, “the United States is fully prepared to do business with him if he is the popular choice.”