At a ceremony on the margins of last week’s Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) preparatory committee meeting in New York, the governments of France, the United Kingdom and the United States reversed their long-standing opposition and joined China and Russia in signing the protocol to the Central Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone Agreement. The regional nuclear weapons-free zone (NWFZ)—the world’s fifth—was established in March 2009, following ratification by Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan of the Treaty of Semipalatinsk, which they signed in 2006. The zone will officially enter into force once the protocol is ratified by the five states that signed it on May 6.

Article VII of the NPT guarantees the right of states to establish such zones, and the United Nations has developed a precise definition as well as generic principles and guidelines for the authors of the relevant agreements. The five treaties establishing regional NWFZs all oblige their states parties to forego research, development, manufacture, stockpiling or other efforts to obtain any nuclear explosive devices in the territory specified by the texts. They further require parties to avoid assisting other countries from undertaking such activities in the region covered by the zone. Conversely, the treaties typically affirm the right of states parties to pursue nuclear energy for peaceful purposes such as research and commerce, providing all their nuclear material and installations are placed under the full-scope safeguards of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). These measures allow the IAEA to verify that all activities at declared nuclear sites have peaceful purposes.

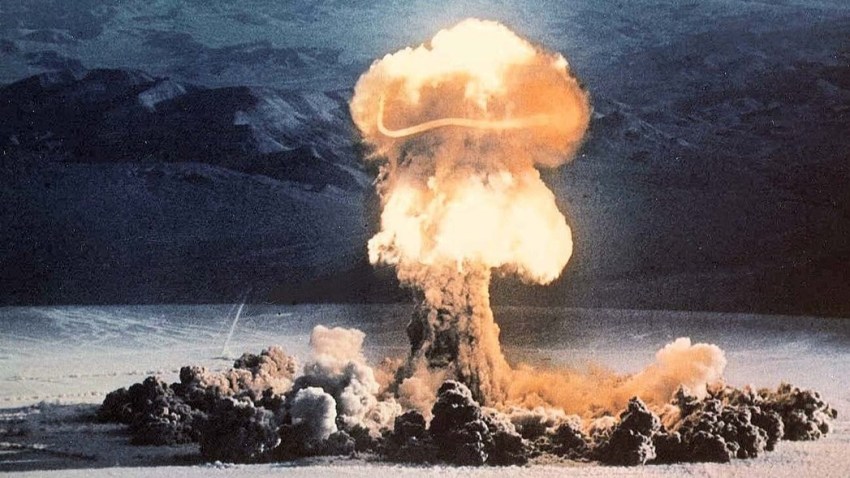

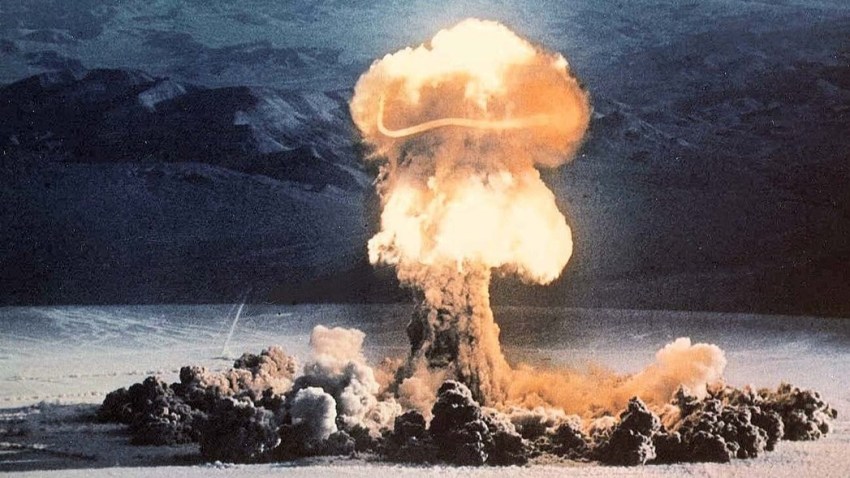

The Central Asian NWFZ is unique in that it adjoins two proliferation-prone regions (South Asia and the Middle East) as well as two NPT-recognized nuclear weapons states (China and Russia). It also includes all five Central Asian countries, whose governments typically pursue divergent foreign policies. One member, Kazakhstan, is the first former nuclear weapons state to adhere to a NWFZ. For the first time, the members also agreed to work to help restore the ecological damage caused by earlier nuclear tests in the region; support the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty; adopt the IAEA Additional Protocol, which gives the agency expanded authorities and access beyond those in the standard full-scope safeguards; and adhere to international standards for the physical protection of nuclear and radiological materials.

NWFZ treaties typically have at least one protocol that specifies the rights and obligations of states outside the zone, which the five countries defined under the NPT as nuclear weapon states—Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States—may sign. One protocol usually commits the nuclear weapons states to refrain from stationing or testing nuclear weapons in the zone or otherwise violate the treaty. Another protocol allows them to offer legally binding assurances not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against NWFZ treaty parties. The non-nuclear states value these so-called negative security assurances as compensation for their abstaining from developing their own nuclear weapons and abiding by their nuclear nonproliferation obligations.

France, Great Britain and the United States have supported the idea of establishing a nuclear weapons-free zone in Central Asia but objected to the agreement’s protocol. Their concerns included the Semipalatinsk Treaty’s seeming to allow Russia to move nuclear weapons in or through the zone within the framework of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, which was created before the treaty was written, and the lack of a clause explicitly preventing other countries, such as Iran, from joining the zone. The fear was that Tehran would join to bolster Iranian claims that it was not seeking nuclear weapons, without necessarily abiding by the terms. After years of intense diplomacy, Central Asian officials managed to persuade their Western counterparts that Russia would not exploit the perceived loopholes and that they would not allow Iran to join. The Central Asian governments hope that the nuclear weapons states will ratify the protocol so that the treaty can enter into force before next year's NPT Review Conference.

Signing for the United States, Thomas Countryman, assistant secretary of state for international security and nonproliferation, said that the Obama administration supports nuclear weapons-free zones as contributing to nonproliferation, peace and security. In its 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, the administration

decided to extend negative security assurances to any state that lacked nuclear weapons, was a member of the NPT and adhered to its nonproliferation obligations, which the Central Asian states do. Countryman added that the Obama administration had decided that the Central Asian zone would not disrupt U.S. security arrangements or military operations, installations or activities.

Vitaly Churkin, Russia's U.N. ambassador, noted that this was the first occasion that all five nuclear weapons states signed a NWFZ protocol simultaneously. This was a hopeful sign that, despite their differences over Ukraine, Syria and other issues, the so-called P-5—referring to the five signing states’ status as permanent members of the U.N. Security council—can still cooperate on important issues. During the past few weeks, the great powers had continued to cooperate on promoting the elimination of Syria’s chemical weapons and in renewing and strengthening U.N. Security Council Resolution 1540, which obliges states to take measures to prevent nonstate actors from obtaining weapons of mass destruction.

When the Central Asian zone enters into force, approximately half the earth’s landmass will be covered by NWFZs. Treaties have created other zones in Latin America and the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, the South Pacific and Africa. Champions of these mechanisms consider them effective arrangements for curbing nuclear weapons proliferation throughout large regions of the globe and hope their spread will promote nuclear disarmament. Governments, nongovernmental organizations and individual experts have called for creating more such zones in other regions, especially Northeast Asia and the Middle East.

Yet, thus far these zones have not had much impact on international nuclear proliferation trends. Countries seem only to join NWFZs after other developments unrelated to their treaties lead them to consider renouncing nuclear weapons options, and no NWFZ has ever induced a state possessing nuclear weapons to eliminate them. So although they are welcome, these zones must continue to be augmented with other measures designed to counter nuclear weapons. In the meantime, the signing of the protocol demonstrates that even in moments of great power tensions, nuclear nonproliferation remains an issue of consensus and cooperation.

Author’s note: The author wishes to thank Mariam Tarasashvili for research assistance for this article.

Richard Weitz is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and a World Politics Review senior editor. His weekly WPR column, Global Insights, appears every Tuesday.