Last week’s visit of Gen. Fang Fenghui, China’s highest-ranking military officer, to the United States both testified to the improvement in bilateral military relations and highlighted the continuing differences between these two military powers.

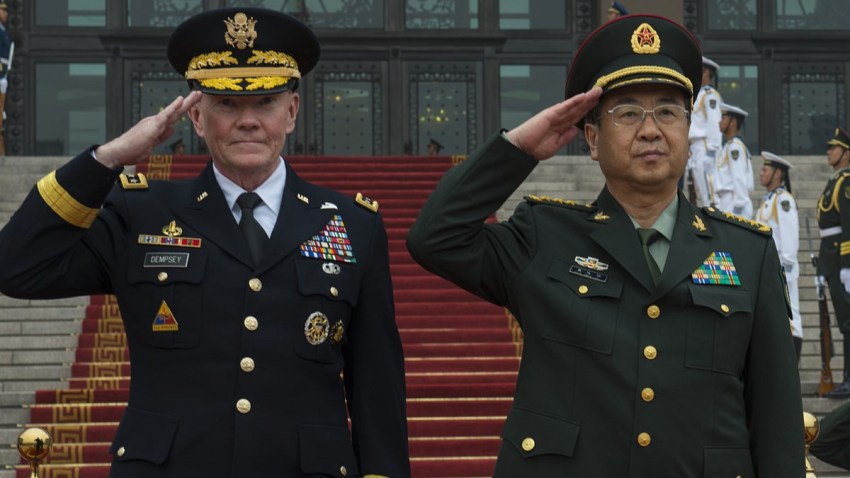

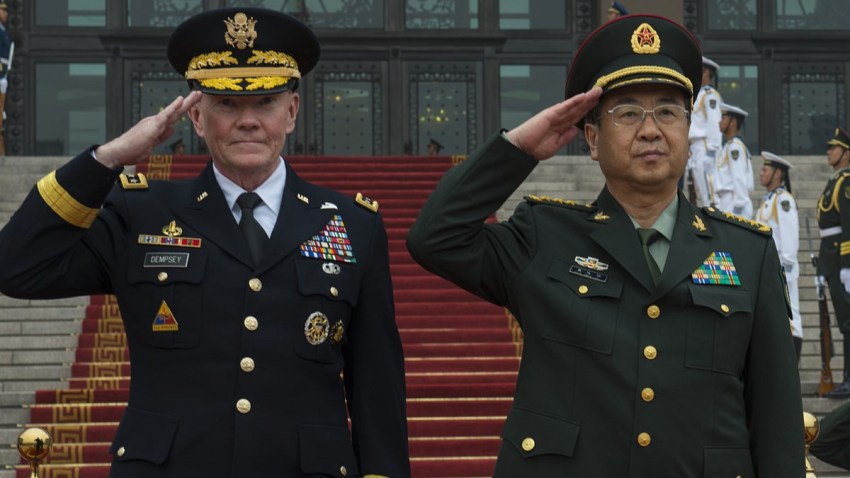

Fang, the chief of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) General Staff, initially spent two days in San Diego, where he met the head of the U.S. Pacific Command, Adm. Samuel J. Locklear, and toured the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan, a littoral combat ship and the regional Marine Corps Recruit Depot. He then traveled to Washington to meet with his U.S. counterpart and official host, Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey, who had conducted a visit to China last year. Fang also conferred with Vice President Joseph Biden and the new deputy defense secretary, Robert Work. (U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel was in the Persian Gulf.) Fang then toured U.S. Army Forces Command in Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, and held meetings in New York.

Fang’s sojourn is the latest in a series of high-level exchanges between the two countries’ militaries. Hagel

spent several days in China last month, his first official visit as defense secretary. He became the first senior foreign official to tour China’s aircraft carrier, met with Chinese military and political leaders and agreed to what the Chinese commentators referred to as a “seven-point consensus” on bilateral defense ties based on the new model of China-U.S. relations endorsed by both countries’ presidents in 2012. In addition to agreeing to hold more exchanges on security issues and to expand practical collaboration, the two militaries committed to establishing a secure video teleconferencing capability and maritime notification system between them and to follow agreed norms of behavior when their navy and air forces operate in each other’s proximity. However, the visit also saw Hagel engage in testy exchanges with some Chinese military leaders over Beijing’s policies toward Japan and other issues.

Last summer, Chinese Defense Minister Chang Wanquan made a four-day swing through the United States that saw him visit the headquarters of U.S. Northern Command and engage in his own frank exchanges with his U.S. counterparts. Other recent high-level defense exchanges have included trips to China by U.S. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Raymond Odierno and U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh as well as a trip to the United States by Adm. Wu Shengli, head of the PLA Navy (PLAN). Dozens of PLAN midshipmen have participated in an exchange program with the U.S. Naval Academy, laying the basis for future partnerships. The two governments also decided to establish regular contacts between the planning staffs of the PLA and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, which could further needed dialogue on anticipating and managing future military contingencies.

Later this year, the PLAN will, for the first time, become a full participant in the U.S.-led Rim of the Pacific exercise (RIMPAC), the world’s largest multinational naval drill. RIMPAC 14, the 24th exercise in the series, will occur from June 26 to Aug. 1 around Hawaii and southern California, and involve some 25,000 personnel from 23 countries. During Hagel’s visit, the two sides confirmed that they would follow this large drill with a separate bilateral medical rescue exercise.

The Chinese government has also tried to respond to U.S. complaints about its limited transparency by releasing more information about its programs and policies, while the Chinese media has offered more details about PLA activities and the units engaged in them. The government and media now also release more information about the country’s new weapons systems.

Of course, one consequence of this increased transparency is to make more evident the differences between the two countries’ national security establishments. In particular, whereas in the past the Chinese tended to downplay diverging views by emphasizing common interests and the possibility of “win-win” outcomes, now they don’t hesitate to frankly address differences.

This new situation was in evidence last week. In his Pentagon press conference with Fang,

Dempsey said, “We had a refreshingly frank and open discussion on our mutual concerns and differing opinions.” With respect to the tensions in the South China Sea, Dempsey cautioned that provocative actions could result in confrontations and called for resolving disputes “through dialogue and international law.” Dempsey warned “about second- and third-order effects” in which maritime clashes can move ashore, as with the anti-Chinese protests in Vietnam.

For his part, Fang called on Americans to “hold an objective view” on China’s territorial disputes and recognize that other countries are seeking to exploit Washington’s Asia-Pacific rebalancing strategy to confront China more aggressively, citing in particular the Vietnamese resistance to Chinese drilling in disputed waters and Japan’s purchase of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. He made it a point to meet with U.S. Flying Tiger veterans who fought alongside Chinese forces against Japan in World War II, which allowed him to tell his Pentagon audience that “it is important to keep in mind that we must defend what we have achieved in the Second World War, and prevent a revival of militarism.”

Although Dempsey skirted the issue at his Pentagon press conference, an anonymous U.S. official told Reuters that China’s new

confrontation with Vietnam, following earlier clashes with

Japan and

the Philippines, “is raising some fundamental questions for us about China's long-term strategic intentions.” Beijing, the official said, was establishing a “pattern” of advancing territorial claims through coercion and intimidation, which “raises questions about our ability to partner together in Asia or even bilaterally.”

The highly visible disagreements between U.S. and Chinese officials are disturbing, but they do reflect what Fang described as the mutual recognition that “our two militaries are very important in maintaining the peace and stability in the region.” Exposing differences helps militaries better understand each others’ tactics, techniques and procedures and thereby avert miscalculations, miscommunications and unsought military confrontations.

Yet the unresolved issues of

U.S. arms sales to Taiwan, U.S. military operations close to China’s territorial waters and airspace and congressional restrictions on U.S. defense technology exchanges with China remain sources of Chinese concern. Furthermore, Chinese analysts complain that, whether deliberately or not, the U.S. stance of professing neutrality regarding Beijing’s territorial disputes is misleading since Washington is in fact backing a status quo established when China was too weak to enforce its claims. In Beijing’s view, Washington is also now taking actions, such as encouraging Japan’s more assertive defense policies and negotiating a new security pact with the Philippines, that make these U.S. allies more confident challenging China’s claims, even though China’s military power has grown sufficiently to allow Beijing to press its claims more vigorously.

Meanwhile, Russia’s success in seizing territory from Ukraine has led China’s neighbors as well as the U.S. to fear that Beijing will now try to do the same in Asia. U.S. officials have therefore taken a firmer stance in public to avert Chinese actions that could precipitate an unsought physical clash later.

After years of halting progress, U.S. efforts to promote both bilateral military contacts and transparency by China regarding its military activities and outlook seem to be gathering momentum. The challenge now is finding ways to manage the differences that increased contact and transparency make even more evident.

Richard Weitz is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and a World Politics Review senior editor. His weekly WPR column, Global Insights, appears every Tuesday.