After nearly six years, Rio de Janeiro’s Police Pacification Units (UPPs) appear to be faltering. Since the beginning of the year, multiple categories of violent crime have risen across the city, and with the spotlight on Brazil due to the upcoming World Cup soccer tournament, the program is now facing unprecedented levels of criticism and scrutiny. Many pundits and journalists are arguing that the pacification program is no longer effective. Meanwhile, public security officials are calling the recent escalation in crime a temporary setback in an otherwise successful effort to combat powerful drug trafficking gangs. In truth, neither of these two characterizations accurately represents the various successes and more recent shortcomings of the pacification program.

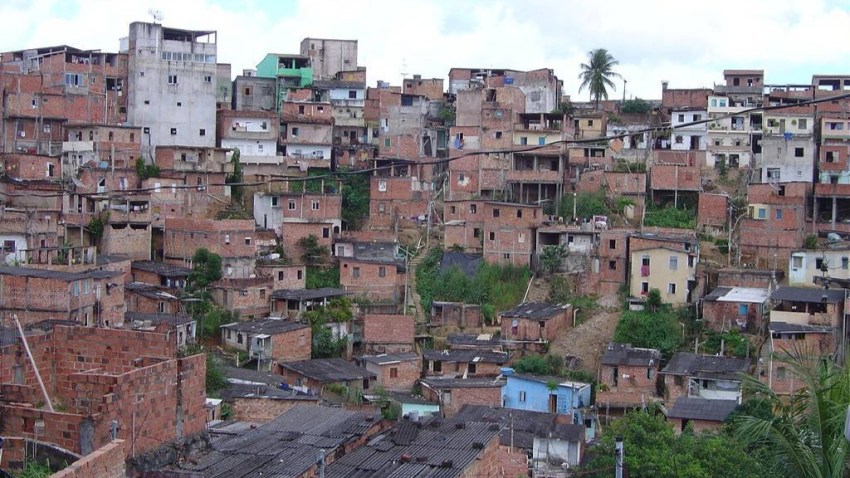

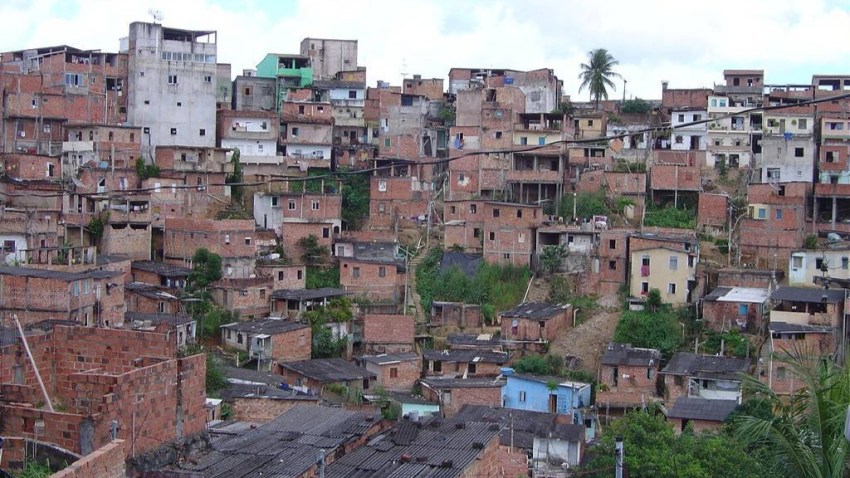

Rio’s Police Pacification program began in 2008 with the plan to wrest control of many of the city’s roughly 1,000 slums, or favelas, from drug-trafficking gangs and install permanent community policing units in these neighborhoods.

As of the end of May 2014, the program has reached approximately 264 separate favelas, benefiting an estimated 1.5 million residents.

The success of the program over the first several years surprised even those with high hopes. Levels of gun violence decreased precipitously in pacified neighborhoods. According to the Institute of Public Security (ISP), the city’s homicide rate

fell nearly 40 percent from 2008 to 2012, accompanied by drops in several other types of violent crime. Moreover, the ability of the state to provide services and infrastructure improved drastically, although these areas remain underserved.

Another major initiative of the pacification program was the reform of abusive and corrupt police institutions. For this reason, pacification police are all newly recruited, better paid and trained in human rights and community policing strategies. So far, more than 9,000 police have completed this training. Accordingly, the number of civilians killed by police in Rio de Janeiro dropped to 405 in 2013, down from 1,330 in 2007, according to the ISP.

However, 2014 has seen the undoing of many of these gains. Again according to official statistics released by the ISP, in the first three months of 2014, the number of intentional homicides rose 22 percent from the same period the previous year, a difference of 262 deaths. In addition, the number of civilians killed by police rose by more than 60 percent over the same period, and 30 police have been killed so far this year, which is quickly approaching the total for all of last year. But these aggregate numbers belie the varying effectiveness of pacification projects in favelas across the city.

Although they are referred to monolithically, the term “favela” applies to incredibly diverse environments. Some favelas contain only a few hundred residents while others can house tens of thousands. In some, poverty is rampant while others are little different than many lower income neighborhoods of the city. Some are located on the sides of steep hills overlooking picturesque beaches near the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods, while others inhabit largely rural or industrial territory far from the city center. Moreover, the types of relationships that local drug gangs maintain with communities can vary drastically. Clearly UPPs confront very different public security situations depending on the favela they work in, and in order to understand the outcomes of pacification units we must differentiate between them.

For the first several years, pacification focused on favelas located on the steep hillsides surrounding Rio’s beaches, wealthier neighborhoods and the downtown area. These favelas are generally smaller, have greater access to services and are often less poor than favelas in other regions of the city. And while some cases have been more problematic, the relative success of the pacification program in these areas is well-documented. In fact, for some of these communities, residents’ major fear is not continuing violence but rising prices due to the arrival of wealthy foreigners and Brazilians who have begun the process of gentrification.

The favelas of the northern zone, on the other hand, are far more populous, poorer and, over time, have been far more violent than their counterparts to the south. These favelas were always going to be a tougher test of the pacification program. Comando Vermelho, the largest and most powerful of the gang factions, has controlled the majority of these territories, maintaining extremely large and embedded networks for several decades. Over the past two years, the majority of the UPPs installed have been in this area of the city. Relatively frequent, low-level violence between Comando Vermelho members and police has marked many of these pacification projects.

In addition, the rapid expansion of UPPs over the past two years and continuing violence in some of these communities has changed the pacification strategy. Instead of focusing on the long-term goals of community policing through fostering relationships between police and community members while improving access to public services, the program has increasingly focused on containing violence through more intensive and militarized policing. Such a strategy will not reduce violence in the long term and cannot effectively combat the drug-trafficking gangs. The drug factions rely on the tacit if not outright support of favela communities, and a more brutal and oppressive police force will only strengthen local gang factions by sewing distrust in the pacification project itself.

The recent upsurge in violence in Rio has encouraged reformers and critics of the program, but an end to pacification or its further militarization would be disastrous. Public security officials must reinvest in the community policing strategy even in the face of difficult and violent circumstances. Newer strategies for working with communities and fostering trust in pacification police, such as integrating and empowering local NGOs and local politicians as well as rededicating the program to providing improved public services, will go a long way toward this end. It is likely that low-level violence will remain for the short term in some of these communities, but this should not make us lose sight of the significant strides that pacification has made since 2008.

Nicholas Barnes is a doctoral candidate in comparative politics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. For the past year, he has been living and conducting dissertation field research in Complexo da Mare, a recently pacified group of 16 favelas in Rio’s northern zone. His research is funded by the National Science Foundation, Fulbright-Hays Dissertation Program and the Social Science Research Council’s Drugs, Security and Democracy and International Dissertation Research Fellowship Programs.