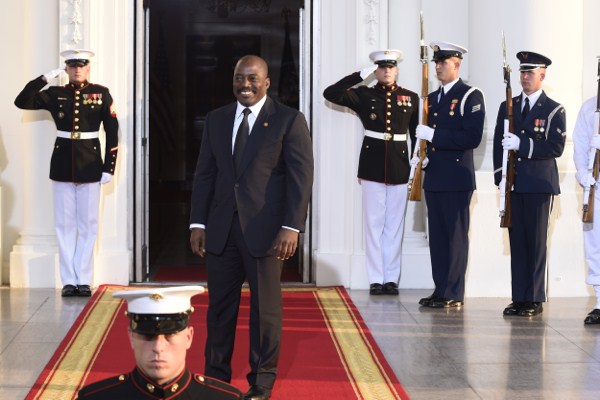

On Sept. 27, street demonstrations in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) drew significant if not overwhelmingly large crowds. The target of the protesters’ ire was President Joseph Kabila, whose loyalists had spent a busy summer testing public opinion on a controversial issue: amending or even replacing the country’s constitution to remove presidential term limits. The subject is of more than academic interest to Kabila, who is fast approaching the end of his final term in office, having assumed the presidency upon the death of his father in 2001 before winning elections in 2006 and 2011. On the question of constitutional change, however, the national mood was unequivocal: a loud rejection of the idea, from civil society, opposition politicians and even some members of the ruling coalition, the People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD). Undeterred by this discouraging response, the president’s advisers have pushed on regardless.

Ever more convoluted semantics have been deployed to chip away at Article 220 of the Congolese constitution, which states that presidents can only serve a maximum of two five-year terms and—for added protection—prohibits any reversal of this clause. The president’s cheerleaders acknowledge this inconvenience but argue with a straight face that there is nothing to stop Article 220 or even the constitution itself from being changed or revoked.

Kabila has remained customarily silent while this debate has played out, but some of his actions suggest that the foundations are being laid to face off the almost inevitable public disorder that would greet the establishment of a monarchical presidency. These include a major reorganization of the military announced in September, in which some of his most trusted generals received promotions, notably Gabriel Amisi Kumba—also known as Tango Four—who gained notoriety when the United Nations accused him two years ago of selling weapons to rebel groups in the east of the country.