In an unusual New York Times Magazine single-story issue titled “Fractured Lands,” journalist Scott Anderson provides a sweeping look at the Middle East, through portraits of subjects from Iraq, Syria, Egypt and Libya. His conclusions are mostly gloomy, although some brief moments of human resilience and hope appear. One can debate his analysis of state failure, and of how much weight to give to U.S. policy, particularly since the 2003 invasion of Iraq, in explaining the current unraveling in some key Arab states. But even with some disagreements, a big takeaway is the vital role that journalists play in making sense of a messy world.

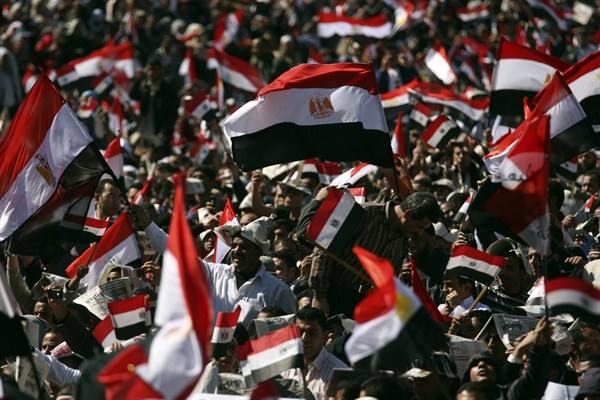

Anderson and photographer Paolo Pellegrin spent a year and a half trying to unravel the story of the Arab world’s upheavals since the Arab Spring of 2011. Their long-play reporting gives deep context, spanning the political evolution of the region from the early 1970s and the political awakening that took place in Egypt five years after the devastating Six-Day War with Israel, to the successes of the self-described Islamic State in 2014, and the enduring chaos and violence in its wake.

Anderson uses the journalistic device of storytelling, honing in on the personal travails of six individuals, to illuminate broader trends and the changing mindsets of people caught up in the confusion of the post-Arab Spring disorder. While the personal story technique is particularly suited to the YouTube and Facebook preferences of millenials, it has its limits, since even the selection of the personal stories can risk inadvertent bias, and access to foreign journalists can in turn become the story. It’s very tricky to be a completely objective observer when the method of observing is intensely personal.