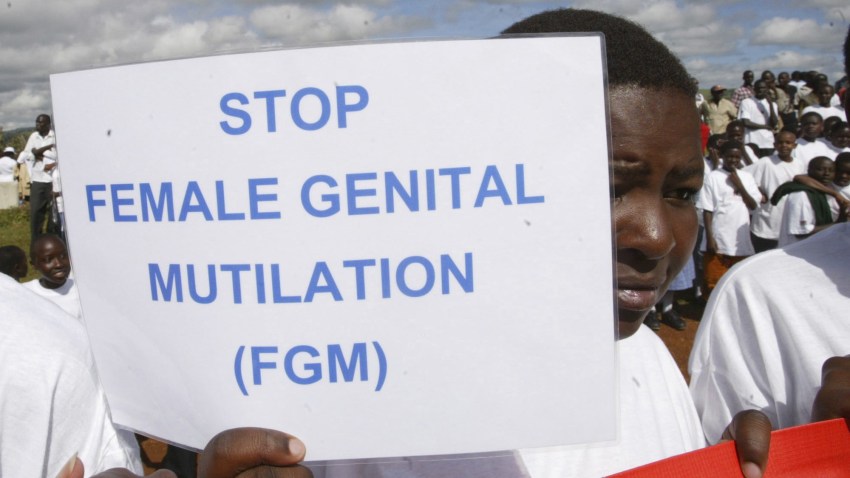

When Sudan announced in April that it would officially criminalize female genital mutilation, or FGM, the news was met with a burst of support and celebration from international observers and activists. UNICEF said the ban signaled a “new era” for girls’ rights, calling it a “landmark move” in a country where around 88 percent of women and girls aged 15 to 49 have undergone genital mutilation.

The measure, which amended the criminal code to make performing FGM punishable by up to three years in prison, was immediately hailed as a sign of hope for the country’s fragile transitional government, formed in the wake of the mass protests that unseated long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir last year. “This is a massive step for Sudan and its new government,” Nimco Ali, a British-Somali FGM survivor and founder of the Five Foundation, a global anti-FGM group, told The New York Times. “They are showing this government has teeth.”

But by the time the ban was fully ratified in July, warnings from more skeptical activists had tempered the celebrations. The legal ban on its own, they said, would not reduce the prevalence of FGM, much less end gender inequality in Sudan.