Around the world, states locked in conflict with jihadists are trying to devise policies to reintegrate disillusioned militants into society. In Nigeria, a program targeting defectors from the violent extremist group Boko Haram offers a window into the promise and pitfalls of such efforts.

For the past 12 years, Nigeria has struggled to quash a violent insurgency waged by Boko Haram in its northeast. Although a 2015 military offensive put the jihadists onto the back foot, the federal government recognized that it would not be able to defeat the insurgency solely through force. It therefore decided to explore nonmilitary ways to erode Boko Haram and, after the group split roughly five years ago, its two successor factions—which I will refer to collectively here simply as Boko Haram.

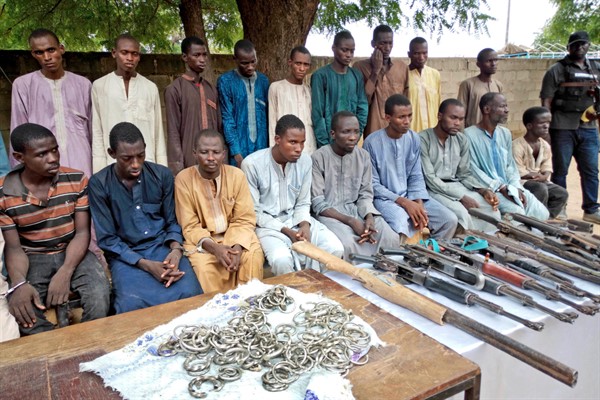

In 2016, the government created Operation Safe Corridor to encourage defections from the group by providing opportunities for “low-risk insurgents” who surrendered to reintegrate into society. The Nigerian military runs the program from a repurposed youth services building in the town of Mallam Sidi in northeastern Gombe state. Here, people identified as Boko Haram defectors generally spend six months following so-called deradicalization programs, which include literacy classes, psychosocial support, professional skills and exposure to visions of politics and religion that contrast with Boko Haram’s ideology.