This month marks the centenary of the Sykes-Picot treaty, a French-English agreement to establish areas of control and influence in the Arab lands of the Middle East after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The milestone has stirred up resentments and a sense that the flailing states of the region never really existed as coherent geographic entities. But changing borders is not easy, and even if one could draw a better map of the Middle East, it would not solve its deepest sources of distress.

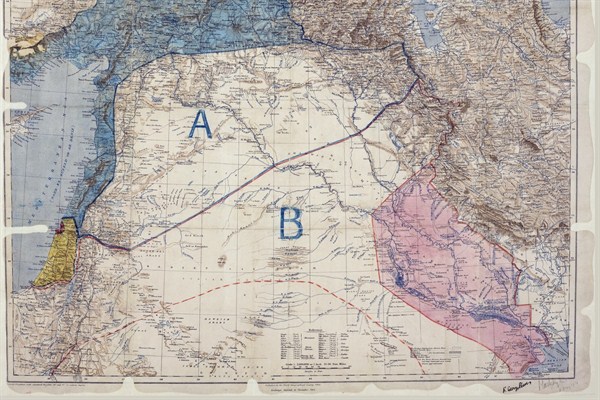

Much is being said about the 100th anniversary of the Sykes-Picot agreement, a minor event in the chaotic period surrounding the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. Sir Mark Sykes, a British diplomat, and Francois Georges-Picot, a French lawyer and diplomat, were tasked by their governments to draw a map that would accommodate both countries in the vacuum left behind once Ottoman civilian and military forces were withdrawn to the new state of Turkey. They designated areas from the Mediterranean coast to the border of Iran, west to east, and from the Turkish border to the Red Sea, north to south, which would fall under British or French influence and control. They established a two-tiered system: “influence” in the hinterlands and “control” in the major cities and productive lands.

In fact, the map they drew in 1916 bore little resemblance to what actually happened, and there is a danger of reading too much into the event. In the minds of many Arabs, nonetheless, the two names evoke the deepest anti-colonial sentiments and a desire to blame all the failings of recent decades on that historic injustice. After violence and bargaining, the borders of modern Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Jordan do not align well with the Sykes-Picot map, but the map somehow remains an inflexion point in the history of the region.