Last week, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi completed a tour of Eritrea, Kenya and Comoros, continuing a tradition dating back three decades by which Chinese foreign ministers open the diplomatic year with a trip to Africa. The visit—which comes just over a month after the conclusion of the eighth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, or FOCAC, held late last year in Dakar, Senegal—illustrates how China’s engagement with African countries is evolving. Beijing is apparently ready to play a bigger role in mediating some of the region’s conflicts. Whether those efforts will pay off is an open question for both China and its partners on the continent.

Wang’s tour comes amid a period of increased jostling for influence among foreign powers in the Horn of Africa, a strategically important region on the continent. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Turkey have all increased their involvement in the Horn’s internecine rivalries in recent years. More recently, an Israeli delegation met this week with Sudan’s military rulers. U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Molly Phee and the newly appointed U.S. special envoy for the Horn of Africa, David Satterfield, also visited Sudan this week for meetings with pro-democracy activists and military leaders, as part of an effort to bolster a United Nations-led dialogue among various stakeholders to end the political standoff in that country.

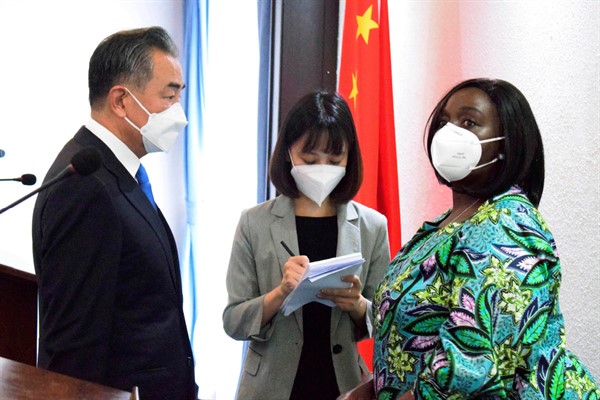

Wang’s trip was notable for his announcement during his stop in Kenya that Beijing will appoint a special envoy for the Horn of Africa to provide support for a peace process within and among the countries of the region. The embrace of a more proactive diplomatic role in such a strategic region suggests that Beijing is keenly aware of the ways its diplomacy and global image have suffered in recent years, particularly due to the so-called “wolf warrior” approach of its envoys and the “debt-trap diplomacy” it is regularly accused of engaging in.