Gabon, a small but oil-rich country on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa that is home to around 1.7 million people, will vote for president on Aug. 27. The main candidates are incumbent President Ali Bongo Ondimba and former African Union Chairman Jean Ping. A victory for Bongo, whose father, Omar Bongo Ondimba, was president of Gabon for more than 40 years, would reinforce patterns of dynastic succession in small African countries that are ostensibly democracies, but in reality autocracies.

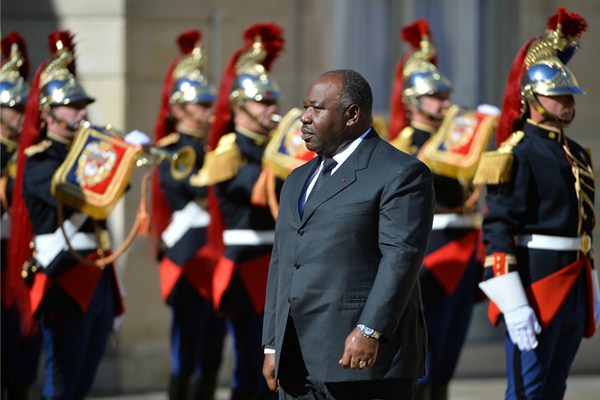

Omar Bongo ruled Gabon from 1967 upon the death of his predecessor, Leon M’ba, the country’s first president after its independence from France. Unlike many African peers who took power in the late 1960s and 1970s, Bongo did not stage a military coup, but like his peers he consolidated power through a single-party state. When many African countries experienced the “third wave” of democratization in the 1990s, involving demands by workers, students and civil society activists for free elections and free association, Bongo survived where some other autocrats fell. He allowed elections, but won them with increasingly large majorities. Upon his death in 2009, authorities organized new elections. His son, Ali Bongo, won with a plurality of the vote, defeating opposition leader Pierre Mamboundou and a defector from the ruling party, Andre Mba Obame.

Gabon’s political history resembles that of Togo, across the Gulf of Guinea, where Gnassingbe Eyadema ruled the country from 1967 to 2005, winning controversial elections in the 1990s and 2000s before passing power on to his son, Faure Gnassingbe. The younger Gnassingbe weathered a constitutional controversy over his succession, but then won a hastily organized election in 2005 and went on to win re-election in 2010 and 2015. The Togo example bodes well for Ali Bongo’s prospects for remaining in power. Protests in Togo in 2005, like protests in Gabon in 2009, did not prevent dynastic successions from occurring.