Migration from Africa to Europe is a hotly debated topic. Headlines about migrants crossing the Sahara Desert or the Mediterranean Sea appear regularly in major international newspapers, most infamously in April, when at least 1,000 migrants died on two capsized ships between Libya and Italy. In Brussels, European leaders meet frequently to discuss policy responses to irregular border crossings and migrant deaths at sea, time and again advancing cooperation with North African states as a potentially successful strategy. But reporting has mainly focused on the European perspective, while North African states’ policy approaches and civil societies’ attitudes toward irregular migrants have largely been ignored. This perspective is essential, however, to fully grasping the migration dynamics unfolding in the region and to working out sensible policy solutions.

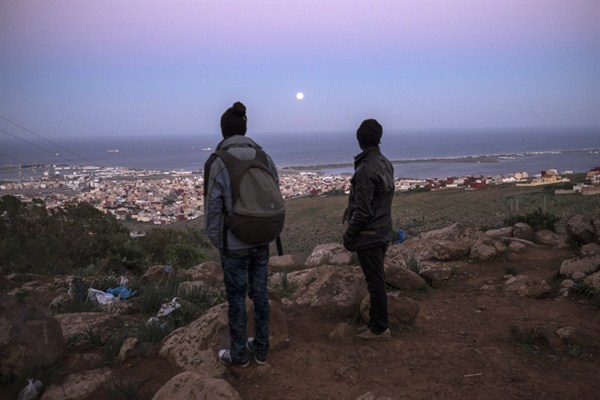

Morocco, in particular, is a key actor in this Euro-African migration system. Over 3 million Moroccans and their descendants currently live in Europe, and thousands of migrants from Asia and Africa arrive in Morocco each year, both to settle there and to prepare for migration to Europe. Morocco’s land borders with the Spanish enclave cities of Ceuta and Melilla on the Mediterranean coast increase its attractiveness for Europe-bound migrants. For European countries, especially France and Spain, Morocco is therefore a crucial partner in migration control. Since the 1990s, these countries have signed multiple bilateral agreements covering border control cooperation, readmission of irregular migrants and preferential access for Moroccan students and workers.

Morocco’s political stability in recent years contributes to making it a privileged partner for Europe. Although the country has not seen the turmoil caused by the Arab Spring in other parts of North Africa, 2011’s pro-democracy “February 20 Movement” and related demonstrations against rising unemployment did challenge the political status quo. As a result, a new constitution was adopted by referendum in July 2011 that increased—at least on paper—human rights and empowered the prime minister and government, without touching the royal prerogatives that form the foundation of Morocco’s political system.