Thirty-six years after the 1979 revolution that overthrew the entrenched Somoza dynasty, Nicaraguans still fill Plaza La Fe in Managua to celebrate Liberation Day festivities every July 19. While to some it may look like an exercise in grand nostalgia, supporters of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) and President Daniel Ortega view the revolution as an ongoing process. Yet some question how far the current administration has drifted from the guiding principles of the revolution and claim he is building a dynasty of his own.

Ortega’s Return and the Consolidation of Power

After being voted out of power following the 1990 presidential election, Ortega lost subsequent presidential contests in 1996 and 2001, making him the FSLN’s sole presidential candidate throughout the party’s history. The conditions for his return to power in 2007 were created by a pact he struck in 1999 with then-President Arnoldo Aleman of the Constitutionalist Liberal Party (PLC). The deal ultimately enabled the FSLN and the PLC to pass legislation that both increased the vote threshold required for political parties to participate in the legislature and lowered the percentage required to win the presidential vote to 35 percent. Though the deal was originally envisioned as a power-sharing pact, Aleman’s subsequent political fall due to corruption charges left Ortega, and the FSLN, without a formidable challenger.

Since returning to power as president in 2007, Ortega has been no stranger to controversy. After being elected by only 38 percent of voters to a term that many expected to end in economic disaster, he was re-elected with more than 62 percent of the vote in 2011. Should he run for re-election next year, he will surely win handily. He owes his popularity to the success of popular social programs and improvements to the economy. At the same time, his political opponents and some outside observers are highly critical of Ortega and the FSLN’s domination of Nicaragua’s political institutions.

Since 2006, the FSLN has steadily increased its vote share for all elected offices, even as corruption allegations in the 2008 municipal elections resulted in the loss of U.S. and European aid. While the level of alleged fraud was fairly nominal, the allegations served to underscore the opposition’s arguments about bias in the country’s electoral tribunal. Controversy also surrounded the 2011 elections. In response to a petition filed by Ortega and FSLN mayors, a court decision found the constitution’s provision on term limits to be “not applicable.” This decision enabled Ortega to run for a third term, though the opposition continued to question the constitutionality of Ortega’s candidacy. While he was re-elected by a significant margin, some in the opposition still refuse to accept the legitimacy of his presidency. Additionally, the refusal to accredit some domestic election observer groups and limitations and delays on accrediting international observer groups only added fuel to the fire.

Opponents liken Ortega to Anastasio Somoza, calling him a corrupt dictator. Allegations of fraud in the 2011 legislative elections, in which the FSLN won a majority with 62 seats, heightened concerns about the integrity of the country’s electoral process and neutrality of political institutions, such as the electoral tribunal and the judiciary. The FSLN’s majority has allowed it to pass laws and make key administrative appointments with little or no consultation with opposition parties. This includes constitutional reforms introduced in late 2013 and passed in January 2014 with minimal opposition support. Though these reforms were fairly wide-ranging, including commitments to community-based policing and setting a gender quota for elected offices, critics focused on changes that centralized power by eliminating term limits, granting the president the power to rule by decree and reducing the presidential vote threshold to a simple plurality.

The resulting political imbalance has left the opposition with virtually no leverage in the legislature with regard to either policy or appointments. Opposition frustrations are heightened by the alliance between the Ortega administration and the business sector, represented by the Superior Counsel of Private Enterprise (COSEP), which critics claim amounts to an extra-parliamentary body. And while COSEP has sometimes sought to balance Ortega’s policies, it has effectively replaced the electoral opposition in that role. Recent protests by opposition leaders and confrontations with police at the country’s electoral tribunal underscore the tensions between the opposition and the FSLN as the country prepares for national elections in November 2016, when Nicaraguans will elect the president, vice president, 90 members of the National Assembly and 20 representatives to the Central American Parliament.

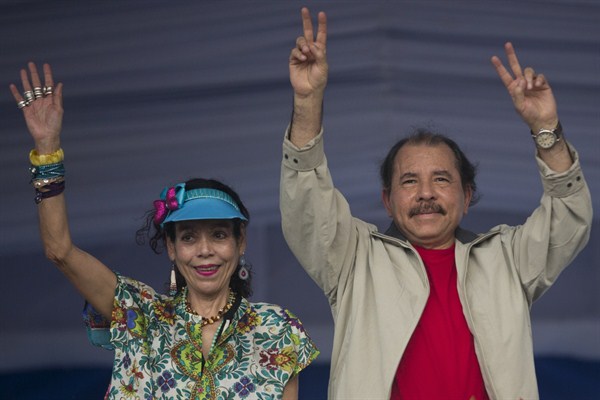

Many presume that either Ortega will run for—and win—a fourth term, or that he will be succeeded by his wife, Rosario Murillo, or their son Laureano. Such prospects only heighten critics’ claims of dynastic rule. Murillo has been a controversial figure in Nicaraguan politics for reasons that are as much personal as they are political. Her very public support for Ortega following sexual-abuse allegations by her daughter, Zoilamerica Narvaez Murillo, damaged her reputation. And her flamboyant fashion sense and new-age spirituality were initially not well-received; rumors abounded that she might even be a witch. Over time, however, she has managed to propel herself into becoming the most popular public figure in the country. Her support for social programs and self-crafted image as the country’s caretaker have gained her countless followers. Her lively aesthetic is now embraced. Colorful, illuminated metal structures known as “trees of life” dominate Managua’s roadways, and Murillo’s face is now as omnipresent on government advertisements as the president’s. But even her critics acknowledge that she is also a skilled politician, defeating many of the old FSLN rank and file in internal power struggles. She reportedly runs Cabinet meetings and controls government communications. A recent New York Times profile described her as “Nicaragua’s First Comrade,” though many believe she is the real power behind the throne.

All of this has made for a particularly polarized political environment, much of it revolving around Ortega himself. Some supporters, referred to as Danielistas or Orteguistas by opponents, outwardly adore him and talk of near-absolute faith in his government, while detractors bear a hatred of him that borders on irrational. Finding a neutral appraisal of his administration can be challenging to say the least. Both sides have legitimate complaints, but they represent completely different narratives. For example, while the opposition cites the Ortegas’ purchase of multiple television channels as evidence that they control the local media, a quick glance at the daily papers suggests the limits of this alleged control. The daily La Prensa, for instance, often refers to him as the “unconstitutional president.”

That said, analysts rightly note that Nicaraguan politics are decidedly less pluralistic than they were a decade ago, as the FSLN has come to dominate the country’s political institutions. While this is true, it has as much to do with the opposition’s corruption and incompetence as it does with the FSLN’s political maneuvers. It seems unlikely at this point that any opposition party will be able to mount a serious challenge in 2016, and merely attacking Ortega is unlikely to gain traction with voters.

This is because, whatever critics might think, Ortega remains very popular, and not just among the rank-and-file FSLN base, but also among independents and some members of the opposition. A March M&R Consultores poll showed that Ortega had an approval rating of 77 percent, bested only by his wife, whose approval rating was 83.1 percent. The overwhelming majority of respondents, almost 72 percent, approved of Ortega’s management of the economy. Moreover, Nicaraguans have the second-highest levels of satisfaction with democracy and support for democracy—meaning that they prefer democracy to other forms of government—in Central America.

It should be of little surprise then that Nicaraguan institutions also boast higher approval ratings than their regional counterparts. In particular, the national police rank among the country’s most trustworthy institutions, and the force’s director, Aminta Granera, enjoys an approval rating of over 70 percent, making her one of Nicaragua’s most popular public figures. This is in large part due to the fact that Nicaragua is the safest country in Central America, with a homicide rate of 8.7 per 100,000—a stark contrast to neighboring El Salvador and Honduras, with homicide rates in 2014 of 69 per 100,000 and 68 per 100,000, respectively. The country’s successful community-policing program is widely considered to be a model for others.

The police’s reputation has recently come under heavy criticism, however, following a botched anti-narcotics operation in which officers opened fire against a misidentified vehicle, killing a woman and two children. Such instances are much less common in Nicaragua than in some other Central American countries, but no less disturbing. In a region where police and security forces operate with impunity, it’s remarkable that nine of the police officers involved in the shooting were sentenced to jail for negligent homicide. Still, the shooting has become fodder for the opposition, which has demanded Granera’s resignation, referring to the incident as a massacre.

A “Market Economy with a Preferential Option for the Poor”

To understand Ortega’s popularity, it is important to understand the extent to which the economic and social climate has improved since his election in 2006. When the FSLN returned to power in 2007, it faced the effects of 17 years of neoliberal economic reforms that followed the country’s devastating civil war. Measures imposed in the 1990s had succeeded in undoing many of the social gains of the revolutionary era, including improved literacy rates and school enrollments. While the policies reduced inflation and brought some growth to the economy, the benefits were unevenly dispersed. Many expected that Ortega, in his zeal to restore these social welfare programs and given his criticisms of “neoliberal imperialism,” would pay less attention to managing Nicaragua’s economy. Yet, by 2011, Nicaragua posted the highest growth rate in the region at 4 percent and continues to outpace its Central American neighbors, with the exception of Panama. Under Ortega, GDP increased 74 percent from $6.78 billion in 2006 to $11.8 billion in 2014. Nicaragua has experienced record investment for the past five years; exports have expanded; and there have been significant improvements in socioeconomic indicators.

The secret to Nicaragua’s success is the FSLN’s approach to economic diversification. Since returning to office in 2007, Ortega has maintained Nicaragua’s agreements with the International Monetary Fund—though it currently has no loan program—and the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), and signed new trade and investment agreements with Panama, Taiwan, Russia and Chile. He also notably joined the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA)—a regional integration scheme initiated by Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez and Cuba’s Fidel Castro as an alternative to neoliberal trade agreements—in 2007. While ALBA is a political entity, joining was as much a matter of practicality as it was an exercise in ideological solidarity. Nicaragua had been crippled by a severe energy crisis, resulting in extensive rolling blackouts throughout the country. Membership in ALBA has provided access to cheap Venezuelan oil through the PetroCaribe scheme; technological assistance, including generators and a $3.5 billion refinery; and low-interest loans through the ALBA Bank to fund development projects. In 2010, Nicaragua received more than $500 million in oil discounts and aid from Venezuela, amounting to about 7.6 percent of GDP.

Though there is little doubt that Venezuelan oil and aid have been vital to Nicaragua’s recent economic successes, diversified sources of trade and investment have also played an important role in the country’s development. While the FSLN, as the political opposition, opposed CAFTA when it was being negotiated, it has embraced the trade agreement—now known as CAFTA-DR since the Dominican Republic joined—while in power. Nicaragua’s exports to the United States grew 71 percent between 2006 and 2011, and in 2013 the country enjoyed a $1.7 billion trade surplus with the U.S., an increase of almost 8 percent over 2012. Though trade with Venezuela has also increased significantly since 2007, the United States remains the main destination for Nicaraguan exports, receiving about 30 percent of them in 2011, compared with only 12 percent for Venezuela. In 2013, U.S. foreign direct investment in Nicaragua was more than double that of Venezuela.

The relationship between CAFTA-DR and ALBA is best described as complementary rather than competitive. While the FSLN has accepted CAFTA-DR as an economic necessity, ALBA provides an important counterbalance to neoliberal policies. Presidential economic adviser Bayardo Arce, who claims that Nicaragua’s economic policy is more pragmatic and less ideological than in the past, describes the current economic program as a “market economy with a preferential option for the poor.”

In addition to maintaining the trade relationship with the United States, the administration has also been courting new investors, as demonstrated by the recent bilateral investment treaty with Russia. In fact, Nicaragua is increasingly recognized as a sound investment prospect, and was twice named by the World Bank’s Doing Business Report as the best country in Central America in several investment categories, including investor protection. Additionally, the Latin Business Chronicle has consistently ranked Nicaragua among the top five most globalized countries in all of Latin America in recent years. In 2011, combined foreign investment from a range of countries, including Canada, Brazil, Korea, Spain and Mexico, nearly doubled to more than $960 million. Free-trade zones have expanded, accounting for $2.4 billion in exports in 2014 and generating as many as 100,000 jobs. Mining, though certainly controversial in the region, also attracts investors. Much of this investment has been facilitated by legislation passed since 2007, which has won Ortega praise from the business sector.

Some worry that the dependence on ALBA will prove to be disastrous should the current regime in Venezuela change. It is a serious cause for concern, which is why the Ortega administration has vigorously promoted other avenues for trade and investment. It’s also worth noting that Nicaragua seeks to free itself from dependence on foreign oil. Despite its access to cheap oil through Venezuela’s PetroCaribe program, Nicaragua has invested heavily in renewable energy. According to a recent International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) study, Nicaragua received more than $1.5 billion in renewable energy investments from 2007 to 2012, the largest per capita investment in Latin America. Renewable energy, including wind, geothermal, hydro and biomass, now generates half of Nicaragua’s electricity, and the government plans to increase that to 90 percent in just over a decade. There is even potential for Nicaragua to export energy to its neighbors in the region.

Improvements in Social Indicators

In addition to oil, ALBA membership also opened the door to Venezuelan aid and access to short-term, low-interest loans, which have been vital to the FSLN’s social programs. Neoliberal reforms implemented throughout the 1990s resulted in a sharp decline in quality-of-life indicators that had improved under the Sandinista government, as successive governments cut vital social safety nets. Between 1993 and 2005, poverty was reduced only 2 percent despite an increase in per capita income of 33 percent. It subsequently increased 2 percent from 2001 to 2005, despite a 7 percent increase in per capita income.

Nicaragua is still the second-poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Approximately 42.5 percent of the population lives in poverty, and the numbers are even higher in rural areas. And although the poverty rate has decreased since 2009, extreme poverty increased by almost 2 percent between 2012 and 2013 when export prices fell, a reminder of how sensitive the economy remains to external fluctuations.

Since returning to office in 2007, Ortega has implemented a number of policies aimed at reducing poverty and inequality. Some of these include programs like Zero Usuary, providing microloans to the rural poor; Zero Hunger, providing seeds, livestock, materials and training to women in rural areas; and CRISSOL, providing loans for small business and farms. Other policies include canceling school fees and providing free school lunch for children in public schools; distributing housing materials such as zinc roofing to impoverished households; and providing housing for the marginalized, among others. The result has been declines in poverty, maternal mortality and child malnutrition, and gains in literacy, school enrollment and the empowerment of local communities. Access to electricity has also improved, with 43 percent more households connected to the grid than in 2006. While some question whether some of these programs are sustainable or will impact poverty or inequality in the long term, they have made Ortega very popular. They have also raised accusations of clientelism, as critics charge that the programs overwhelmingly benefit FSLN supporters.

The government has also placed significant emphasis on addressing gender inequalities. Nicaragua ranked sixth in the World Economic Forum’s 2014 Global Gender Gap Index. Women hold 39 percent of seats in the legislature and 57 percent of Cabinet positions, including the minister of defense and the police commissioner. The Zero Hunger and Zero Usuary programs target women in particular, in an effort to promote economic independence and reduce poverty among female-headed households. Casas Maternas, or Maternal Houses, have been built throughout the countryside to provide health care and refuge to expectant mothers, while police stations dedicated to women and children seek to provide assistance to vulnerable populations. The country also boasts one of the most comprehensive gender-violence laws in the region, though in reality the government lacks resources to sufficiently support it. An amendment to the law requiring battered women to engage in mediation with their abusers sparked outrage among women’s rights groups. Additionally, the country’s strict abortion law, which allows for no exceptions to the blanket ban, stands in contradiction to the advances made toward women’s health and reproductive rights. This is especially troubling given that Nicaragua has one of the highest adolescent pregnancy rates in the world. Despite improvements, gender-based violence also remains a serious problem.

The Canal as Fault Line

Impressive economic expansion notwithstanding, Nicaragua remains a small, poor state. To generate enough growth to move the country out of poverty, the government believes it needs a megaproject, and there is perhaps no development project more deeply ingrained in the Nicaraguan psyche than that of an interoceanic canal. The government is currently in the planning stages for one—an 18-foot-deep, 173-mile-long canal that will cost between $40 billion and $50 billion, making it the world’s largest construction project if it is indeed built. There have been dozens of proposals to bring a canal to Nicaragua over the years, so it remains to be seen if this one will finally become a reality. If all goes according to plan, the canal will be operational by 2020.

The current project dates back to 2012, when Nicaragua passed a law, known as Law 800, creating the legal basis for the interoceanic canal. In June 2013, Law 800 was annulled and replaced with Law 840, which granted a concession to Hong Kong firm HKND, headed by billionaire Wang Jing. The Ortega administration believes that the canal construction will create 50,000 jobs, as well as additional employment within the canal zone for business and infrastructure projects.

The proposed canal has been controversial for a number of reasons. The lack of public consultation and legislative debate about the project has undermined its legitimacy. At least two public employees with expertise on the issue, who are at odds with the canal proposal, have found themselves out of a job, based on the author’s personal knowledge. Furthermore, the public still awaits the economic-feasibility and environmental-impact studies that would better help to assess the canal’s viability. Critics also argue that the concession law, which gives HKND claim to property within and outside the canal zone, violates Nicaragua’s sovereignty and is unconstitutional. While the original law guaranteed 51 percent of shares in the canal’s holding company to the state, the new law gives the state only 1 percent of shares with 10 percent more transferred every decade. This means that Nicaragua won’t gain full control of the canal for 100 years.

Beyond the legal issues, there are serious concerns about affected populations and environmental impact. The project is almost certain to displace populations living within the proposed canal zone; while the exact number is unknown, estimates of displacement range from 30,000 to 100,000 people. This particularly contentious issue has stoked clashes between residents and security forces during survey studies, and local communities have been organizing against the canal. Indigenous groups living in the proposed canal zone, including the Rama, have taken their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), claiming that the proposed canal violates both the land rights and territorial autonomy of those living within the South Atlantic Autonomous Region (RAAS). While the government maintains that all displaced residents will be compensated, the level of compensation has not been determined.

The environmental consequences of the proposed canal are particularly worrying. The excavation would require moving some 4.5 billion cubic centimeters of earth and threatens to destroy the fragile ecosystem of Lake Cocibolca, also known as Lake Nicaragua. Some critics say the amount of dredging necessary to route the canal through the shallow lake would mitigate any benefits. Additionally, scientists worry that the contaminants released by dredging will significantly reduce the quality of the lake’s water, which is currently suitable for irrigation and drinking. It would also surely destroy the tourist attractions in the lake, such as Isla Ometepe, a bioreserve and popular tourist destination.

Foreign Policy in a New Era

Historically, Nicaraguan foreign policy under the FSLN was pragmatic. During the 1980s, the government sought to cultivate relationships with a wide variety of states. It supported nonalignment and used its membership in international institutions in an attempt to generate support for the revolution—and end the painful U.S. embargo. This tendency, as evidenced by Nicaragua’s diverse trade and investment relationships, remains evident today.

The Ortega administration has remained vocal in its opposition to what it perceives as interference, particularly on the part of the United States, in the affairs of other states. This was part of the government’s explanation for refusing to accredit some domestic and international election observers in the 2011 elections. At the 2009 Summit of the Americas meeting, Ortega notoriously provided President Barack Obama with a rather pointed 50-minute history lesson on U.S. intervention in the region. He was also an outspoken critic of the June 2009 coup that overthrew President Mel Zelaya in Honduras, which was widely condemned throughout the region, as well as in the OAS and the United Nations. Ortega openly accused the United States of plotting the Honduran coup and claimed that the U.S. would do the same in Nicaragua if it had the means. And while his leadership on Honduras was widely praised, his support for old U.S. foes, such as former Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, and his burgeoning relationships with current U.S. adversaries, such as Iran and Russia, have certainly ruffled a few feathers.

That said, none of this has necessarily been problematic for U.S.-Nicaraguan relations. Ortega’s vocal support for regimes that are not friendly with the United States has been characterized as “manageable tensions” by one former official, who stated that the level of rhetoric was even negotiated between the two parties. So long as Ortega provided stability and cooperated on key issues, such as drug interdiction, then his relationships with Chavez, Cuba and Libya were not problematic.

Another characteristic of Nicaraguan foreign policy under the Ortega administration has been the interest in cultivating diplomatic and political ties that allow access to unconditional aid. As such, Ortega’s relationships with Venezuela and Russia aren’t merely a matter of ideological affinity. These donors do not condition the aid they provide upon any criteria for good governance or democratic rule of law, as has been the case with the United States and Western Europe. To that end, some suggest that Ortega’s relationship with Venezuela has facilitated a decidedly less pluralistic foreign policy than he might have pursued otherwise—and reduced accountability for good governance practices required by liberal democratic donors.

Ortega’s greatest foreign policy challenge has likely been with neighboring Costa Rica. In 2009, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) rendered a decision on a petition on the San Juan River entered during the Aleman administration that reaffirmed Nicaragua’s sovereignty over the river. Animosity between the two neighbors deepened in 2010, when Costa Rica accused Nicaragua of illegally occupying its territory during a dredging operation near the mouth of the San Juan River. Costa Rica presented its claim to the ICJ, and Nicaragua presented a counterclaim over environmental damages that it alleges were caused by the construction of a Costa Rican road along the river.

Tensions between the two countries became highly personal. Then-Costa Rican President Laura Chinchilla referred to Ortega as her enemy and even marched in anti-Nicaragua protests in 2013, after Ortega publicly joked about a potential Nicaraguan claim to Guanacaste, which was annexed by Costa Rica in 1824. Relations with her successor, Luis Guillermo Solis, did not fare better. Solis skipped Nicaragua in his inaugural tour of Central America. Closing arguments to the court were presented in the spring, and the parties await the ruling.

Another territorial dispute, this time with Colombia, has also complicated regional relations. In 2001, during the final days of the Aleman administration, Nicaragua submitted an application to the ICJ over Caribbean waterways. In 2012, the ICJ ruled in Nicaragua’s favor, although Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos refused to acknowledge the loss of territory. Shortly thereafter, Nicaragua began drilling for oil in the Tyra Bank, a contested area of water off Nicaragua’s Atlantic Coast. Costa Rica joined in protesting the drilling.

Conclusion

Daniel Ortega’s return to power was greeted with skepticism, even among some who now support him. While notable improvements in the economy and the implementation of social programs have significantly increased his popularity and support for the government, questions about transparency and the FSLN’s dominance of institutions have fueled critics’ ire.

There is no doubt that, socially and economically, Nicaragua is in a better position than it was in 2006. Increased investment and growth have brought new opportunities, and many believe that the proposed canal could be the key to the country’s salvation. Poor and working-class Nicaraguans view the state as a positive force, citing programs that alleviate hunger, improve access to credit and education, and provide health care and job training. Many in the countryside and in working-class neighborhoods of Managua profess not to understand the “bourgeois” preoccupation with elections and issues of constitutionality. This was particularly true of the 2011 controversy surrounding Ortega’s eligibility as a presidential candidate. Rather, they see a government dedicated to addressing their needs. To them, this is the essence of democracy.

But concerns about transparency and corruption are difficult to dismiss and should not be overlooked. There may well have been a time when the FSLN believed that it needed such a preponderance of power to ensure that its economic and social objectives remained secure. After all, the party had seen them dismantled before. But increasing demands for transparency and dialogue in advance of the 2016 elections provide an opportunity for Ortega and the FSLN to demonstrate that the revolution has the capacity to be inclusive of its critics as well as its supporters.

Christine Wade is associate professor of political science and international studies at Washington College in Chestertown, Md.