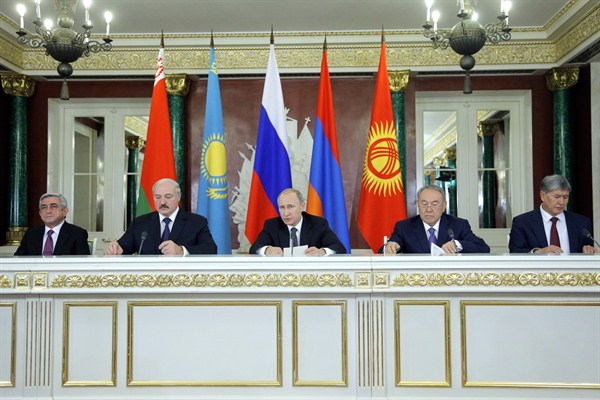

Earlier this week, during his address to the United Nations General Assembly, Russian President Vladimir Putin touched on a topic that was easily overlooked amid his claims about Ukrainian and Syrian sovereignty. “Contrary to the policy of exclusiveness, Russia proposes harmonizing original economic projects,” Putin intoned, citing “plans to interconnect the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), and China’s initiative of the Silk Road Economic Belt.” Putin promptly turned to other topics, letting any further details about linking the troubled Kremlin-backed EEU—made up of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia—with one of the two principal components of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitious “One Belt, One Road” strategy for new trade and transportation networks across Eurasia.

The merger, originally proposed in May, stands as a last-gasp effort at relevance for the EEU. For Moscow, avoiding further discussion of how it will work in practice may be the best current tack. Should observers delve further into the details of this putative integration, it would quickly become clear that the move is far from a merger of two equitable partners, or another step in a burgeoning Sino-Russian axis. Rather, linking these two massive economic regional projects, if and when it actually happens, further highlights both the EEU’s futility and China’s pre-eminence within Central Asia. Instead of a parlayed partnership between Moscow and Beijing, the proposed union will be more evidence of China’s economic primacy over a reeling Russia.

As it is, the Kremlin never intended the EEU—an outgrowth from a prior Customs Union comprising Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus—to merge with China’s Silk Road Economic Belt. The EEU’s current iteration is a far cry from the apolitical post-Soviet trade bloc that Kazakhstan’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, first proposed in 1994. Now 10 months old, the EEU represents Moscow’s foremost attempt at geopolitical consolidation within the former Soviet space. Moscow’s proposals for a common currency, unified passport and codified defense alignment may have faltered, with Kazakhstan and Belarus taking every opportunity to stall Moscow’s politicization of the group’s economic structures in the aftermath of Russia’s actions in Ukraine. But those measures were always more about protectionism than international integration. For Kyrgyzstan and Armenia, the other states since cajoled by Moscow into joining the EEU, membership has resulted in higher tariffs and new barriers to trade relationships they once enjoyed, including, for Kyrgyzstan, re-export trade with China.