On June 23, the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States discussed OAS Secretary-General Luis Almagro’s report invoking the group’s Democratic Charter against Venezuela. Almagro’s report underlined not only Venezuela’s democratic deficits—including the lack of separation of powers, the jailing of political opponents, and the crackdown on protest—but also scarcities of food and medicine, inflation, and dramatic rates of crime and violence.

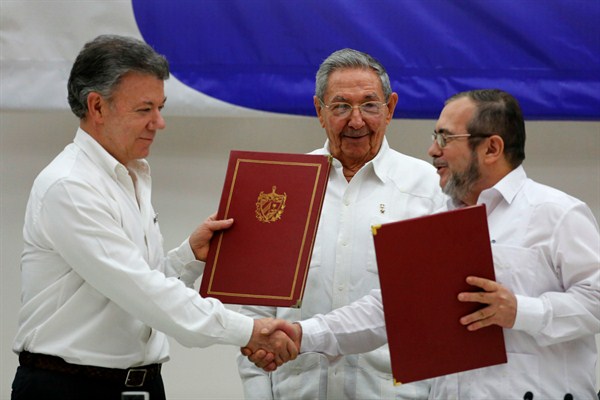

At the very same time, 1,800 miles to the south, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and Rodrigo Leon Echeveri, the leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), signed a historic cease-fire agreement calling for an end of hostilities in their more than 50-year conflict and laying the groundwork for the demobilization and disarming of the guerrilla group. Both Santos and Leon thanked Venezuela for its role in the three-year peace process. Embattled Venezuelan President Nicholas Maduro was in attendance.

These contrasting, simultaneous images are potent symbols of the complexity of Venezuela’s position in the Western Hemisphere. On the one hand, regional leaders had an open and robust discussion of Venezuela’s downward spiral, a milestone given South American countries’ long-term resistance to foreign interference. On the other hand, Venezuela rightly basked in the success of one of former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez’s key diplomatic legacies: the peace process in Colombia.