Guatemalans vote Sunday in what looks like one of the most unpredictable elections in their country’s recent history. Across an extremely fragmented field, a total of 19 candidates, whittled down from the original 24, are competing for the presidency. Nearly two dozen political parties are also chasing seats in the 160-seat, single-chamber Congress and in 340 municipalities around the country, which, with a population of more 17 million, is the largest in Central America—and where a landmark fight against corruption has taken a U-turn.

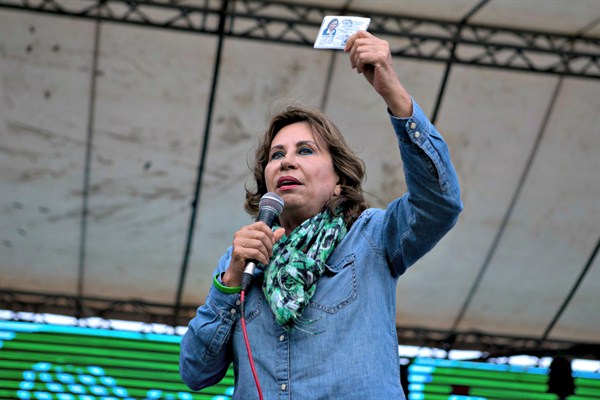

In a field otherwise skewed to the center and to the right, opinion polls favor former First Lady Sandra Torres, an experienced but controversial leader of the social-democratic National Unity of Hope party, known by its Spanish acronym, UNE. Trailing her are a range of challengers jockeying for position on the center right, led by Alejandro Giammattei of the Vamos party, Roberto Arzu of PAN-Podemos and Edmundo Mulet of the Guatemalan Humanist Party. Those three are considered contenders to make it through to a second-round runoff against Torres, set for Aug. 11 if, as seems likely, no candidate gets 50 percent or more of the vote in the first round.

Still, it is probably best to expect the unexpected. The elections are uniquely volatile for many reasons, but perhaps most of all because corruption and crime remain deeply entrenched in the Guatemalan political system. Back in the heady days of 2015, it looked as if Guatemala was making historic progress to clean things up. The United Nations-backed and largely U.S.-funded International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, known by its Spanish acronym CICIG, worked with local prosecutors to uncover a major kickback scheme in the national tax collection agency and customs office, known as La Linea. Investigators found that it was led by none other than President Otto Perez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti, who were both forced to step down, arrested and put on trial. Both are still in prison today.