The first victim in March was Julio Gutierrez Aviles, the president of a local community action group in Campoalegre, a small town in the rural, mountainous department of Huila in western Colombia. Gutierrez had taken part in recent protests to support Huila’s farmers, trying to make a difference in a region that has long been seen as strategic by various armed groups in Colombia. According to local news, he was on his way home when he was attacked by a group of men, who shot him without saying a word and then left his body on the road.

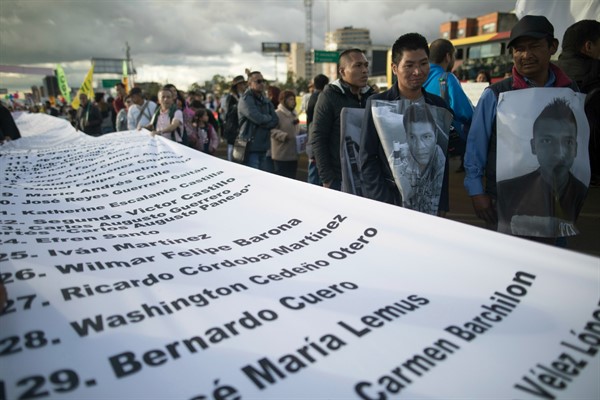

In the days that followed Gutierrez’s killing, a social leader from the troubled southern region of Putumayo was also murdered, along with two indigenous leaders from departments along Colombia’s Pacific coast, a women’s rights activist from Bolivar in the north, and two local politicians and three ex-councilors from across the country. Later in March, there were three more murders that appeared politically motivated: of a trade unionist; a former combatant from the recently demobilized Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, who was helping other ex-combatants reintegrate into society; and an activist who was trying to help local farmers switch from coca, the base ingredient for cocaine and one of Colombia’s most lucrative exports, to alternative crops.

Even with that death toll, as months go, March was pretty standard for Colombia. Four years ago, the Colombian government signed a controversial peace deal with the FARC to end its insurgency, which had raged for more than five decades and brought the country to its knees. Though the deal led to the demobilization of the FARC, the largest guerrilla group in Latin America, the ongoing killings across rural Colombia make clear that the agreement did not succeed in ending all the violence.