In early December, amid rising tensions between Australia and China, Prime Minister Scott Morrison posted a statement on the Chinese social media platform WeChat to voice his outrage at an incendiary tweet from a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson. Within a day, WeChat, which routinely polices sensitive content on its platform, had blocked Morrison’s post, ostensibly for violating the company’s policies.

It was not the only instance of a foreign official being censored on a Chinese social media platform. The most prominent offenders are WeChat—the largest social media site in China, with over 1 billion active users—and Weibo, a microblogging platform that is similar to Twitter. Sites like these are the only way for foreign governments and their diplomats to reach Chinese audiences online, as the so-called Great Firewall blocks access to nearly all foreign social media platforms, including Twitter and Facebook.

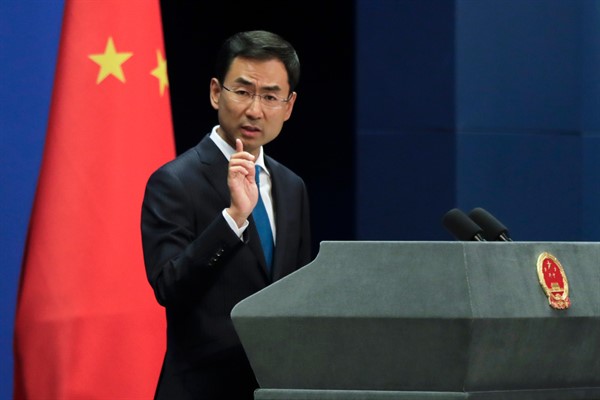

Censorship of overseas content in China is nothing new, of course, but the scale and frequency of the practice has accelerated in recent years. A 2018 report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute highlighted numerous examples, most notably in May 2018, when the U.S. Embassy in China issued a riposte on Weibo to Beijing’s request that foreign airlines identify Taiwan, Macau and Hong Kong as “Chinese territories.” The embassy’s post, which criticized China’s “Orwellian nonsense,” remained viewable on Weibo but only to users with a direct link. The sharing function was turned off and responses were carefully tailored to include only those that reflected the government’s position.