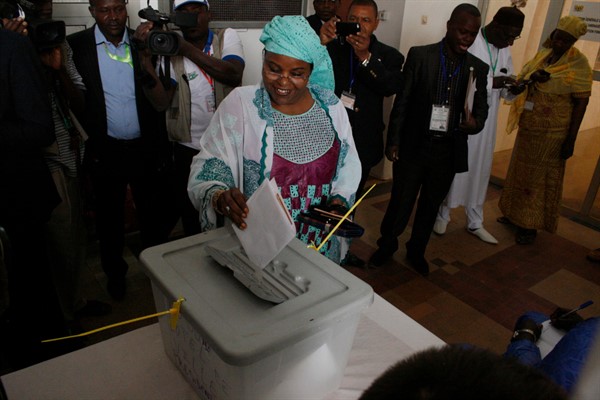

Voters in Niger will return to the polls this Sunday for a runoff election that will determine outgoing President Mahamadou Issoufou’s successor. The subsequent transition will mark the first time in the country’s history that one elected president replaces another. Beyond being a milestone for its democracy, this vote also holds real significance for Niger’s troubled neighborhood, an arid region just below the Sahara Desert known as the Sahel, where political and security conditions have deteriorated in recent years. To Niger’s west, President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita of Mali was ousted in a coup last August, the second in less than a decade; to the east, President Idriss Deby, in power in Chad since 1990, has announced his controversial campaign for a sixth term in office ahead of elections in April.

Niger represents what is surely one of the most challenging governance contexts in the world. Landlocked and arid, it was again dead last—as it has been more often than not—in the most recent Human Development Index rankings, an assessment of quality-of-life indicators produced by the United Nations Development Program. It has one of the highest population growth rates in the world. Its vast territory is a crossroads for both licit and illicit trade and transit networks from sub-Saharan to North Africa and Europe. And, like its neighbors, Niger faces extraordinary security challenges from jihadi and other militant groups in the Sahel’s decade-long crisis that was sparked by the fall of Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi in 2011.

The anticipated political transition that will follow this weekend’s election is all the more remarkable given Niger’s rocky history of democratization efforts since its first transition from military to civilian rule in 1991. In the three decades since, the country has gone from its Third Republic to its Seventh, a trajectory punctuated by three military coups, four transitional governments and five constitutions.