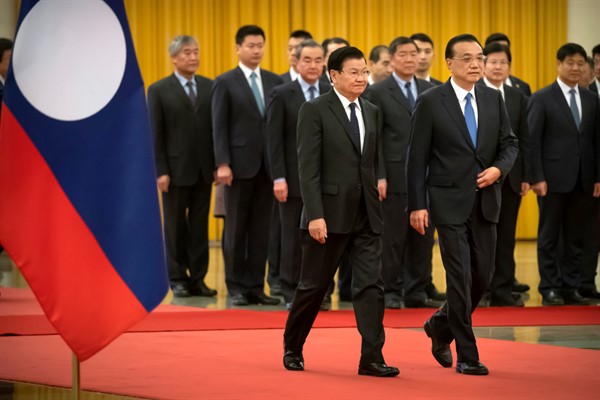

Over the course of three days in Laos in mid-January, more than 750 senior members of the ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party convened in the capital, Vientiane, to elect its political leaders for the next five years. The delegates to the 11th National Congress chose incumbent Prime Minister Thongloun Sisoulith to replace the retiring Bounnhang Vorachit as the party’s secretary general—the most powerful position in Laos’ communist system. If recent precedent is upheld, this paves the way for Sisoulith to also be confirmed as president when a nominally new National Assembly meets later this month.

Elections for the assembly were held on Feb. 21, but the event was something of a sideshow to the party congress, and the country’s 4.3 million eligible voters were scarcely given many options to choose from. Just 224 candidates stood for 164 legislatives seats, most of them members of the LPRP, as the ruling party is known. A handful of independent candidates were permitted to stand, though there is little prospect of change in Laos’ tightly controlled one-party state. The polls also gave voters the chance to fill 492 seats on provincial People’s Councils, from a similarly restricted list of 788 candidates.

The elections, as with January’s congress, were held in person despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Laos has officially recorded only 47 confirmed coronavirus cases in total, but its economy has suffered, as the tourism industry and service sector have been hit particularly hard. The poverty rate is expected to rise amid a decline in remittances. These issues add to the government’s already substantial burden of debts linked to major Chinese-backed infrastructure projects. A $6 billion, 414-kilometer high-speed railway, as well as a number of hydroelectric dams on the Mekong River and its tributaries, are among the costliest. Shoring up the economy will thus be the first priority for Sisoulith as his five-year term gets underway.