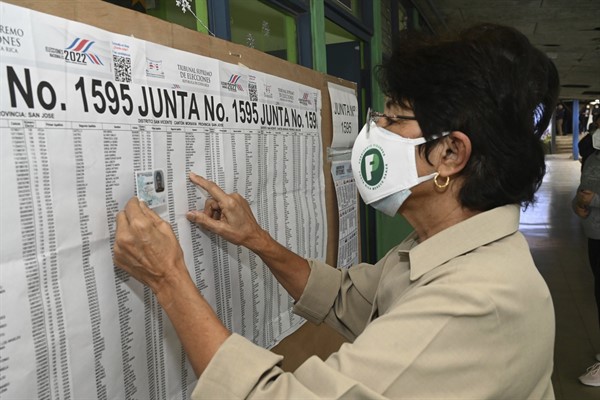

Costa Ricans went to the polls Feb. 6 for the first round of the country’s presidential election, as well as its congressional elections. But with none of the 25 presidential candidates able to reach the 40 percent of votes required to win the contest outright, the country will hold the runoff round in April to decide whether first-place finisher Jose Maria Figueres Olsen or runner-up Rodrigo Chaves will become its next leader.

One of the most stable democracies in Latin America, Costa Rica’s electoral integrity standards are considered to be among the most transparent and fair in the world. But a 40 percent rate of abstention on Election Day may be associated with Costa Ricans’ increasing dissatisfaction with the performance of their democratic institutions—a trend many other stable democracies around the world are also experiencing. Public frustrations over economic instability and inequality, disillusionment stemming from various corruption scandals involving multiple political parties, and widespread vacillation among voters in polls just days before the election might have also contributed to the election’s inconclusive outcome.

The election campaign was dominated by the country’s most urgent problems, including a volatile economy as well as high levels of poverty and unemployment, with the debate over these issues framed within a discussion of whether the state should intervene more or less in the economy. Costa Rica’s elevated public debt and erratic economic growth led outgoing President Carlos Alvarado’s government to negotiate an unpopular $1.8 billion loan agreement with the International Monetary Fund in January 2021 to stabilize the economy. Although poverty decreased compared to 2020 from 26.2 percent to 23 percent, it is still higher than it was before the pandemic started, when it stood at 21 percent. And while unemployment dropped from 17 percent in 2020 to 14.4 percent last year, it nonetheless continues to disproportionately affect women and young people. Perhaps most importantly, the pandemic has accelerated Costa Rica’s most pressing structural issue: the unequal distribution of wealth. Inequality has increased and risks undoing the country’s achievements in improving human development indicators over the past four decades.