This is Part II of a two-part series. Part I examined the reality of freedom and repression in contemporary China. Part II examines the Chinese government and society's struggle to adapt to the information age.

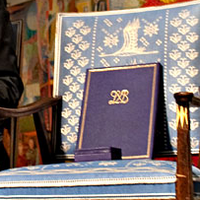

BEIJING -- Following weeks of outraged rhetoric and divisive diplomacy from Beijing, last month's Nobel Peace Prize ceremony was blacked out on most -- but not all -- of China's international satellite channels. The New Yorker's Evan Osnos remarked that "The black screen is a darkly comic relic . . . left over from a time when Chinese newspapers hailed bumper harvests and denounced foreign imperialists. The black screen is reserved for special occasions -- not for the ordinary censorship of news about Chinese-government corruption. The black screen is reserved for a specific kind of unknowing: the denial of something that everyone already knows."

The Chinese response did indeed have elements of the absurd, from the false assertion that "a majority of nations rejected the award" and claims that the Nobel Committee operates "like a cult," to the bungled announcement of its own peace prize, which was awarded before its recipient even knew it existed. International news outlets' Web sites went down, and the domestic Internet slowed to a crawl as government bots filtered content. The dreary ritual of rounding up "known dissidents" took place, and police presence was boosted in urban areas. It was a very Chinese crisis -- one that in most countries would not have been a crisis at all, but which here became the sole concern of nearly every organ of the state for two weeks.