Editor's note: This is the first of a two-part series on the G-20. Part I examines efforts to rebalance the global economy. Part II will appear tomorrow and will examine efforts to reform the global monetary system.

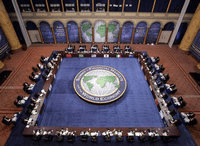

Over the weekend, G-20 finance ministers met in Paris to discuss steps on how to address persistent global current account imbalances that some fear could send the global economy back into recession. From the outset, the meetings reinforced what we already know about the group: Preferences among the members are incredibly diverse, making progress toward cooperation painfully slow. This is exacerbated by the fact that no single economy is able to impose its preferences on the others, and none is willing to bear disproportionate burden for the greater good. In the end, the group reached consensus on a list of legitimate "imbalance indicators" by which each economy may be judged. Yet, as achievements go, this agreement is about as insignificant as they come.

The G-20 apparently decided that in Paris, the bar for success would be set as low as possible. Then again, with such an array of preferences and with fingers wagging in every direction both before and during the summit, the fact that the meetings were held at all might be considered a success.