The NATO campaign in Libya has just begun its second month, and the situation on the ground is not improving. The defenses of Misurata are deteriorating, and rebel forces appear to be falling back from Adjadibya. In spite of the deteriorating tactical situation, however, the leaders of France, the United Kingdom and the United States have formulated in very certain terms the maximalist strategic goals of the campaign: the end of Moammar Gadhafi's grip on power. The basic problem remains one of complete incoherence between strategic goals and operational means. Paris, London and Washington want Gadhafi gone. However, none of the three powers are willing to deploy the forces necessary to topple the Gadhafi regime. They are left with the vain hopes that Gadhafi will simply abandon Libya, or that the rebels will magically become capable of winning the war.

Though the situation on the ground is still unsettled, it is not too early to think about the lessons learned from the NATO intervention in Libya's civil war. Nevertheless, with disturbances continuing across the Arab world, it is worth thinking through not simply the lessons that have been learned thus far, but the disjuncture between those lessons and the ones the international community might have wanted to impart.

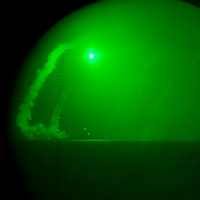

The bombing of Libya was supposed to teach the region's autocrats that the international community would not stand by and watch as they massacred peaceful civilians. While it is likely that some form of this lesson has been imparted, it is not entirely clear that Gadhafi's offensives against Libyan protesters and revolutionaries have "failed." The NATO intervention has thus far been sufficient to prevent Gadhafi from winning a decisive victory, but it is arguable whether Gadhafi's position is worse now than if he had not pursued a military campaign against the rebels. Autocrats in similar positions may also draw the lesson that Western intervention does not spell the end. Gadhafi's ragtag collection of mercenaries and loyalists has done passably well against the air forces of the most powerful states in the world. Indeed, given the fate of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak at the hands of his own military, dictators may conclude that assembling ad hoc, but loyal, security forces is better than building a powerful but potentially disloyal army. The most important lesson for autocrats may be that killing rebels and protesters is best done quickly and quietly.