Since an international tribunal in The Hague ruled in July that China’s claims to the South China Sea had no legal basis and thus violated the Philippines’ maritime rights, claimants to the waters have focused on lowering the temperature on the ongoing disputes. Though this is a welcome respite from years of tensions and has yielded some progress, formidable challenges remain in translating these gains into sustainable solutions for the complex disagreements between China and five other claimant countries—Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam.

Before the tribunal’s verdict, many observers had worried that a lopsided legal outcome for either China or the Philippines would deal a severe blow to international law or spark tensions in the South China Sea. The vital waterway had already endured several years of testy exchanges and ratcheting tensions as a result of China’s growing assertiveness and the other claimant countries’ subsequent reactions. What ended up happening, however, was an unexpected legal verdict that overwhelmingly favored the Philippines but didn’t see tensions rise.

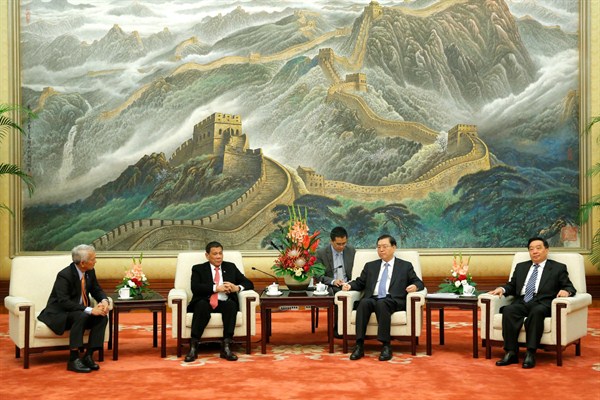

That’s because the verdict coincided with changing political conditions in the Philippines that offered the chance to cool tensions with China—namely, the election of President Rodrigo Duterte, who signaled a desire to set aside the maritime disagreements and reset ties with Beijing in a marked departure from his predecessor, Benigno Aquino III, who had filed the case in The Hague. With Manila appearing to step back from its role as the front-line state on the South China Sea, other Southeast Asian countries were, to varying degrees, also keen to advance alternative areas of cooperation between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN. The United States, which has repeatedly stressed its support for regional initiatives, also cautiously supported these efforts.