After a string of scandals throughout 2014, Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto’s corruption-related troubles haven’t let up this year. A high-profile former governor with close ties to Pena Nieto’s ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has had his vast collection of luxury real estate in the United States revealed, prompting accusations of impropriety, while another former governor is under investigation for embezzling millions of dollars of public funds. The latest examples of graft and perceived conflicts of interest help explain why Mexico still lags behind Chile, Colombia and Brazil, three of Latin America’s most developed economies, in Transparency International’s 2014 Corruption Perception index, and ranks 79th out of 99 in the World Justice Project’s international rule of law index.

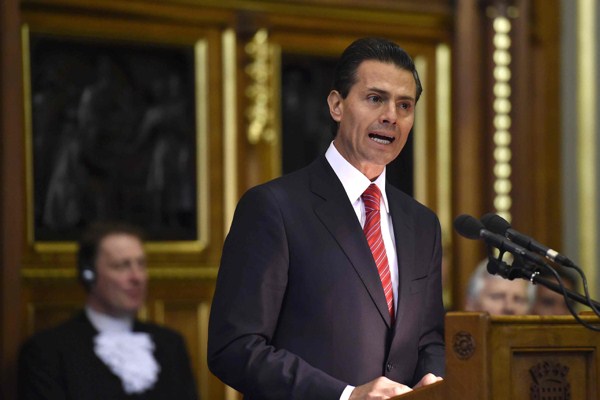

In a surprisingly blunt interview with the Financial Times on Monday, Pena Nieto admitted, “Today there is, without doubt, a sensation of incredulity and distrust . . . there has been a loss of confidence and this has sown suspicion and doubt.” Pena Nieto put the onus on his government to “reconsider where we are headed.”

Concretely, that means actually reforming the rule of law in Mexico and tackling endemic corruption. On paper, Mexico has a well-established track record of dedication to the rule of law and law and order. In practice, though, many observers say that Mexican elites have long consolidated political power into a nominally democratic system that preserves space for serious conflicts of interest. Political dissidents have for decades accused the PRI of abandoning its original progressive agenda and allowing cozy relationships between business and political elites to define the unofficial rules of civic life.