Tension is rapidly accelerating in Antarctic affairs on a range of issues, all of them relating to sovereignty and resources. The tensions include disputes over proposals for new marine protected areas in the Southern Ocean; renewed friction between the U.K. and Argentina over their overlapping claims in Antarctica; significant numbers of countries expressing an interest in exploring Antarctic minerals, despite a ban on mineral extraction; increasing numbers of states trying to expand their Antarctic presence, signaling both heightened interests and insecurities over Antarctica’s current governance structure; and escalating conflict between anti-whaling groups and the Japanese government over whaling in the Southern Ocean.

Combined, these tensions are putting increased pressure on the Antarctic Treaty and a body of subsequent international agreements known collectively as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) that have governed the Antarctic continent and Southern Ocean since 1961.

At the time it was drafted, the treaty represented an innovative approach to defusing potential tensions over sovereignty arising in Antarctica. Seven states claim Antarctic territories; the treaty permits them to maintain those claims, though not to extend them, while also permitting other countries to ignore the claims and to regard Antarctica as an international space. The groundwork for putting together the Antarctic Treaty was forged during the 1957-1958 International Geophysical Year, which launched a program of international scientific collaboration and saw national-based programs stepping up their investment in polar research.

Drawing on that background, the treaty states that Antarctica “should not become the scene or object of international discord” and highlights “freedom of scientific investigation” as a key activity on the continent. From the scientists’ point of view, Antarctica is a perfect laboratory for many areas of scientific research. But from the politicians’ perspective, investing in Antarctic science is a means to signal presence and influence Antarctic decision-making.

In addition to the Antarctic Treaty, a number of other international instruments also govern Antarctic affairs, such as the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Fifty states have signed the Antarctic Treaty, but only 28 -- the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties (ATCPs) -- actually have a say in how the continent is governed. The 22 non-ATCP states within the treaty are effectively “second-class citizens” with no rights other than to observe meetings.

The number of signatories to the treaty and the level of activity in Antarctica have been fairly static since the signing in 1991 of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, also known as the Madrid Protocol, which came into force in 1998. Among other things, the protocol placed a ban on Antarctic mineral exploitation. But in the past two years, two new states, Malaysia and Pakistan, have signed the treaty; Iran has announced its plans to set up an Antarctic base, though it has not yet said whether it will sign the treaty; a rush of new bases have been announced by various ATCPs; and China, South Korea, the United States and Australia, among others, have significantly increased their Antarctic budgets.

Meanwhile, global environmental groups are lobbying governments and attempting to sway public opinion to preserve and extend environmental management in Antarctica. Their concern is not unwarranted. China, South Korea, Russia, India, Belarus and Iran have all

expressed an interest in assessing Antarctic mineral resources; China has taken up significant fishing rights in the Southern Ocean; and Japan has stated that “food security” necessitates its continued whale hunt in the Southern Ocean. The decline of global oil stocks and heightened food security concerns are reawakening global interest in the Antarctic continent and its oceans. Yet with their unwieldy structure, the treaty and its associated instruments appear inadequate to deal with the many new challenges.

The Antarctic Treaty was a product of the Cold War, designed to keep the conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union and their respective allies out of the Antarctic region. It succeeded in that regard, but now, two decades after the end of the Cold War, the Antarctic Treaty looks like an antiquated gentleman’s agreement desperately in need of reform.

Poorer countries are effectively excluded from Antarctic governance because only those nations with recognized Antarctic interests, whether as original claimant states or through established Antarctic scientific research programs, may become ATCPs. The limitations on which states can have a say on Antarctic affairs undermines the political legitimacy of the treaty, which, as with any international instrument, will be measured by the number of states that sign up to it -- and the extent to which signatories respect its principles.

The ATCPs are an exclusive group of states with the resources and scientific infrastructure needed to conduct Antarctic science. National Antarctic bases are in turn a way to signal presence, which could be a key basis for any future ownership claims if Antarctic mineral resources were ever to be divvied up. In 2048, the Madrid Protocol can once again be reviewed by the ATCPs. This review is not automatic -- one of the ATCPs must request it. But judging from the recent behavior patterns of some Antarctic states, finding a government willing to put forward the motion should not be difficult. Many oil-poor states and those that lack guaranteed access to oil through their allies regard Antarctica’s mineral resources as a potential solution to their medium-term energy needs.

But before the ban can be lifted, a comprehensive minerals treaty would have to be in place. This is why environmental groups are already building campaigns aimed at mobilizing global public opinion to support a continuation of the ban on mineral exploitation in Antarctica. It is also why countries, such as China, that are interested in the potential of Antarctic minerals are now engaging in the strategic planning and research that will help construct a new instrument of global governance.

One thing is certain: Antarctica is rich in mineral resources. In a series of reports and maps published in the 1980s, a team of international researchers working with the U.S. Geological Survey divided the Antarctic continent into three major geologic zones: the Andean metallogenic province, which contains mainly copper, platinum, gold, silver, chromium, nickel, diamonds and other minerals; the Trans-Antarctic metallogenic province, which contains what may be the world’s largest deposit of coal, plus copper, lead, zinc, gold, silver, tin and other minerals; and the East Antarctic iron metallogenic province, which contains significant amounts of iron ore, as well as gold, silver, copper, uranium and molybdenum. The key locations likely to have oil and natural gas deposits were identified as the Ross Sea, Weddell Sea, Amundsen Sea and the Bellingshausen Sea, with the Ross and Weddell Seas likely to have significant supplies.

Due to economic, engineering and -- after 1998, when the Madrid Protocol came into force -- environmental and political constraints, this earlier research did not progress much further until recently. Last year, however, China’s annual Antarctic expedition included geologists investigating petroleum deposits in the Weddell Sea. South Korea has been engaged in similar research for a number of years. And as noted, other states have expressed an interest in doing the same. In January 2012, China announced it planned to set up a new coastal base in the Ross Sea region of Antarctica.

Some critics of the treaty say that Antarctica should be run by the United Nations. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, for instance, Malaysia, supported by many other developing countries, unsuccessfully raised this point at the U.N. However, the proposal failed to gain traction due to the stonewalling of Antarctic Treaty stakeholders who opposed it. Malaysia joined the treaty in 2011 and has already signaled it wants to play a reformist role if it is granted ATCP status. However it is at a disadvantage here, as only a significant Antarctic science program, and not its 20 years of political interest in Antarctic affairs, will enable it to participate in Antarctic governance. Other critics argue that a whole new set of international laws applying to all nations, not just Antarctic Treaty members, should govern the continent. Yet even the existing instruments of international governance applicable to Antarctica seem ineffectual in resolving conflicts there.

For example, the treaty and its instruments have little to say on the matter of Japan’s Southern Ocean “scientific whaling,” even though the ever-escalating clashes between Japanese whaling vessels and the boats of the marine wildlife conservation organization Sea Shepherd break existing environmental rules and disturb the peace. From a political perspective, other Antarctic states are also wary of raising this issue through the framework of the Antarctic Treaty System, for fear that the politicking and controversy already surrounding Japan’s whaling program would infect the ATS. The conflicts over whaling in the Southern Ocean also pose a potential hazard to legitimate scientific activities and the integrity of designated Antarctic Specially Protected Areas in the vicinity of the clashes.

This year’s skirmishes between Sea Shepherd and the Japanese boats took place close to several protected areas for vulnerable penguin colonies. In February 2013, the Japanese whaleboat Nisshin Maru rammed the Sea Shepherd boat Bob Barker several times and used stun grenades against the crew, while Sea Shepherd boats returned fire with rancid butter pellets and shadowed the Japanese boats’ every movement, greatly hindering the whale kill. For the first time ever, a Japanese Self-Defense Force boat, the icebreaker Shirase, accompanied the Japanese whaling ships to the Southern Ocean. In addition, a Japanese Self-Defense Force military helicopter based on the Shirase shadowed the Japanese whaleboats as they attempted to refuel in the waters of the Southern Ocean.

This escalation of conflict in the Southern Ocean and near the coasts of Antarctica surely challenges the treaty’s fundamental precepts, which prioritize peace and science and prohibit all military presence in Antarctica and surrounding seas, except for the purposes of logistical support for national scientific programs. The boats’ ramming each other as well as the refueling of the Japanese whaling boats while being harassed by Sea Shepherd boats in the Southern Ocean create environmental hazards, including the risks of an oil spill; if one had occurred, would the ATCPs raise it with Japan under the Protocol on Environmental Protection, or would they just ignore it as they have been ignoring so many other breaches of behavior associated with Japan’s whaling in Antarctica?

Despite the concerns raised by these annual violent clashes over whaling, we can expect that the next Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM), to be held this May in Brussels, will be silent on the issue. ATCMs are pro forma affairs attended by government officials with no mandate to set new agendas. The meetings have consistently failed to address potentially high-conflict issues, such as the claimant states’ Antarctic continental shelf applications to the United Nations Law of the Sea Commission. From the perspective of some nonclaimant states -- China has been the most vocal, but it is not the only one to hold this view -- the claimant states’ submission of information to UNCLOS amounted to an attempt to expand territorial claims on the continent, which is prohibited under the treaty.

The ATCM is also likely to be silent on what, from Argentina’s perspective, appear to be the U.K.’s violations of the treaty. Clashes over sovereignty were the original impetus for the Antarctic Treaty, but it never resolved key points of contention such as the overlapping claims of the United Kingdom, Chile and Argentina. In 2012 and 2013, Argentina raised vigorous protests to what it perceived as the Cameron government’s attempt to extend the U.K.’s presence and jurisdiction in Antarctica by passing new legislation renaming a large chunk of these disputed Antarctic territories Queen Elizabeth Land. But the U.K. is unlikely to face consequences from the ATCM, and nonclaimant ATCPs, such as China, can only continue to look balefully on such behavior.

When controversy does occasionally erupt in ATCMs, the meeting reports notoriously understate the contention. This is because the Antarctic Treaty is a conservative instrument that requires full consensus for all decision-making. This structure enables the established Antarctic players to maintain the status quo, but it does not facilitate addressing new challenges that won’t go away, and in fact appear to be getting more difficult as the years progress.

In many ways the term “Antarctic governance” is in fact a misnomer. There is very little oversight of the various countries active there, and almost no enforcement through Antarctic Treaty System instruments when nations break the governance rules. Instead Antarctic Treaty states are supposed to police themselves by passing national legislation that matches the Antarctic Treaty and by applying this legislation to the activities of their nationals there. The treaty permits and encourages base inspections, but such inspections are not in-depth, and inspectors don’t ask hard questions such as to what extent science is the main activity of the base and whether or not bases follow guidelines on environmental management and reporting. In 2012 it was discovered that Brazil had failed to report to the Antarctic Treaty’s Environmental Protection Committee that a Brazilian oil barge carrying 2,600 gallons of oil had sunk while unloading cargo at the Brazilian Antarctic base. There were no consequences for Brazil’s failure to report the accident or penalties imposed for it having occurred. Such lax enforcement is not unwelcome to many of the relatively newer and rising players in Antarctic affairs, which chafe at the restrictions that environmental protection measures impose on the expansion of their activities.

As more and more states eye Antarctic resources, any perception that some states are gaining advantages by stealth will be resisted by others. This dynamic can result in the blocking or dilution of genuine efforts to protect at-risk habitats. There is a deep lack of political trust among many Antarctic states, as well as a deep conflict of values and interests, that will be hard to reconcile. In November 2012, at the

annual meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), this divide was briefly exposed when Russia, China, Belarus and Ukraine raised vehement objections to several

proposals to set up marine protected areas (MPAs) in the Southern Ocean. A number of other states neither spoke up in favor of nor against the proposed MPAs, exposing the lack of consensus on the issue and uncertainties about the agenda of the nations -- New Zealand, the United States, Australia, France and the United Kingdom -- that proposed them. The countries that opposed the MPAs in 2012 are not intrinsically opposed to marine protected areas; there are already MPAs operational in the Southern Ocean. But it appeared that these new MPAs were perceived by the dissident states as a form of what one Chinese Antarctic diplomat calls “soft presence” -- using environmental measures to restrict the activities of other actors. The protection proposals ultimately failed, and another meeting will be held in Bremerhaven in July 2013 to attempt to achieve a consensus on the issue.

A further unresolved governance issue is the matter of who has jurisdiction over the activities of individuals in Antarctica, especially with regard to citizens of nonsignatory states working there or individuals from signatory states who are engaged in activities on bases or territories under the legal jurisdiction of other nations. This gap, which has never been properly addressed within the treaty, leaves a gray area if criminal or negligent behavior occurs, as may have been the case in 2000, when an Australian scientist died in mysterious circumstances at the U.S. Scott-Amundsen Station, or in 2011, when the yacht of a nonregistered Norwegian expedition sank off the Ross Ice Shelf. Both incidents occurred in New Zealand’s Ross Dependency claim, so in theory the New Zealand police force should have dealt with these matters. But in the case of the 2000 incident, the U.S. Antarctic program did not cooperate with the New Zealand police, and in the case of the ill-fated 2011 expedition, New Zealand had no legal means to prevent the visit or detain its leader when he returned to New Zealand waters in 2012 and launched a second expedition to the Ross Sea area.

The Antarctic Treaty privileges science as the core legitimate activity on the continent and the main justification for states to be involved in Antarctic governance. But tourists now vastly outnumber scientists, with 33,000 tourists compared to roughly 4,000 scientists visiting Antarctica each year. Despite the size of the tourism industry, it is unsatisfactorily regulated within the treaty, and ATCPs have resisted calls for it to be better managed through a new treaty mechanism. Instead, the International Association of Antarctic Tourism Operators has set a voluntary code of practice, which has repeatedly proved ineffective at properly managing the environmental risks associated with taking large numbers of people and boats into the fragile Antarctic environment.

Another underregulated and ever-increasing Antarctic activity is bioprospecting, or the search for valuable materials produced by living organisms. ATCPs have resisted suggestions that the practice be regulated or the idea that any income resulting from bioprospecting belongs to all of humanity under the principle of the common heritage of humankind. Here as on other matters, Antarctic governance privileges the developed world and allots the spoils to those who came first and those who are most powerful.

Much groundbreaking science has come out of Antarctica, such as the identification of the ozone hole; the reconstruction of the last 1 million years of global climate history from ice cores; the establishment of a sustainable management system for Southern Ocean fisheries; the mapping of Antarctica’s subglacial lakes; as well as groundbreaking research into the origin of the Southern Continents. In the next few years we can expect Antarctic science to make further major contributions, with new findings from the neutrino laboratory (ICECUBE) and other major astronomy developments; research that will link the impact of the rise in global sea levels with changes in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet; research on the origin and evolution of the deep ocean fauna; and new findings on Sun-Earth interactions through solar storms.

However, the main goal of these scientific activities for all of the governments engaged in them is meeting their strategic needs, both political and economic. Science is the currency of Antarctic politics; high-level science garners high-level influence, and having at least a basic scientific program in Antarctica is the fig leaf for maintaining a base there. Though many scientists work cooperatively on international projects, each scientific base in Antarctica is run by national programs, and they act as effective diplomatic posts. This approach is extremely wasteful with regard to resources and generates a significantly larger scientific footprint in Antarctica than if scientific activities and environmental protection, as opposed to simply maintaining presence, were truly the focus of Antarctic Treaty partners.

Many of the ATCPs lack sufficient resources to engage in meaningful Antarctic science and fill their bases with support personnel. Many Antarctic science bases, in contravention of the treaty, are essentially military bases. At least three ATCPs are currently openly renting out beds on their bases to visiting tourists, which, while not technically illegal under the treaty, contravenes norms of behavior among signatory states. We should not be surprised, then, if states like Iran say that they, too, want to access the spoils of Antarctica but don’t indicate a desire to sign up to an agreement that effectively discriminates against latecomers and whose principles are frequently ignored, even by established players.

In 1959, when the Antarctic Treaty was negotiated, the main preoccupation of the dominant Antarctic partners was the prevention of the threat of armed conflict spreading to Antarctica. But in 2013 the priorities of the 28 states actively engaged in Antarctica affairs, as well as the more than 170 other states in the world that are technically eligible to engage in Antarctica but are prevented from doing so due to economic barriers, are very different.

The Cold War ended 22 years ago, and political ideology no longer divides the world. Arguably the greatest common global challenges are how to deal with the escalating impact of climate change and the quest for new resources to feed and fuel the world’s growing population. Antarctic science has helped definitively prove that climate change is caused by human activities, but the political solution for climate change issues now lies outside the Antarctic Treaty, in the form of instruments such as a new climate change protocol. Instead, from the perspective of many states, Antarctica now forms part of the answer to our age’s other great question: how to continue to raise the global standard of living when known sources of resources are running out.

A further shift in geopolitics that will impact Antarctic affairs is worth noting. Global economic power has clearly shifted to Asia, with China leading the way. The emerging economies such as China, South Korea and India, along with a re-emerging Russia, are all interested in taking leading roles in shaping new international instruments that will better reflect their national interests. These emerging economies are almost all oil-deficient and lack guaranteed oil supplies, so they are looking for new sources of oil and natural gas in the medium term, when current supplies that are available to them will be exhausted. They also are looking to external sources to resolve food security concerns. Changing ice-shelf dynamics brought about by climate change, the growing cost of fuel, as well as the development of new technology that makes it possible to extract oil in the harsh polar environment are making many states re-evaluate the ban on mineral resource extraction in Antarctica.

The Antarctic Treaty System in its present form is not well-suited to deal with these new priorities. It is questionable whether it will survive another 50 years, and indeed for how much longer the period of relative peace and environmental protection that this treaty secured for the Antarctic continent and its oceans will last.

Anne-Marie Brady is editor in chief of the Polar Journal and editor of “The Emerging Politics of Antarctica” (Routledge, 2012).

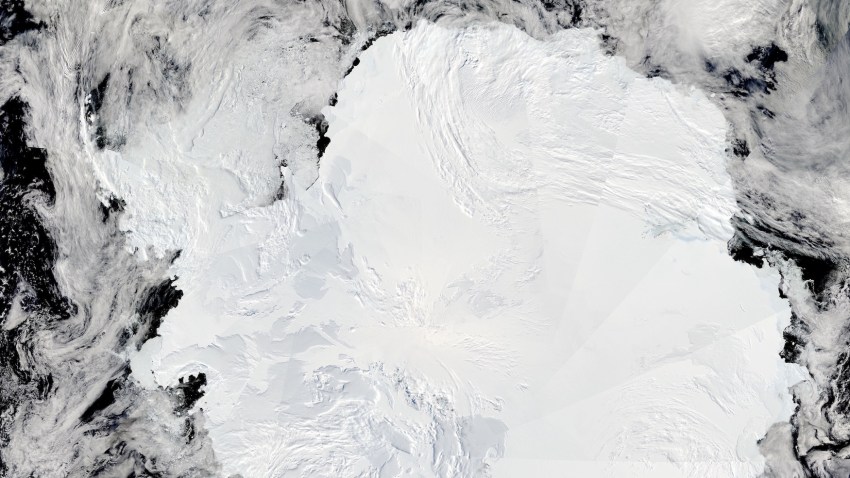

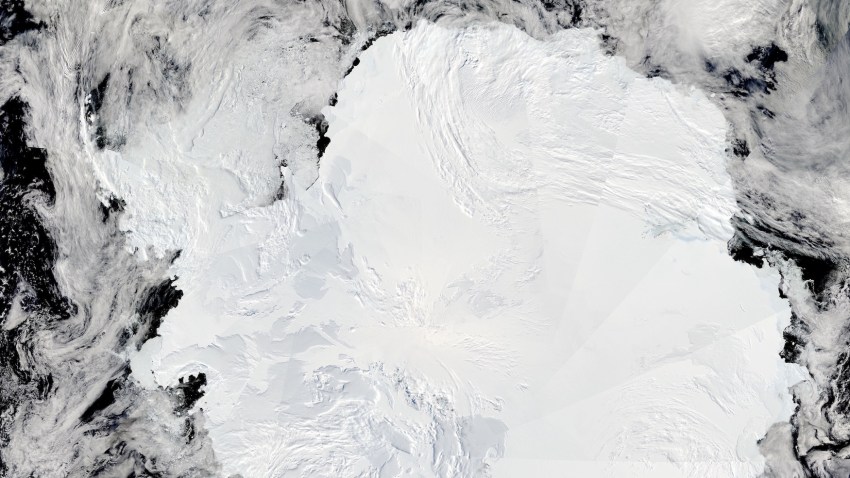

Photo: Researchers in Antarctica in 2002 (NASA photo).