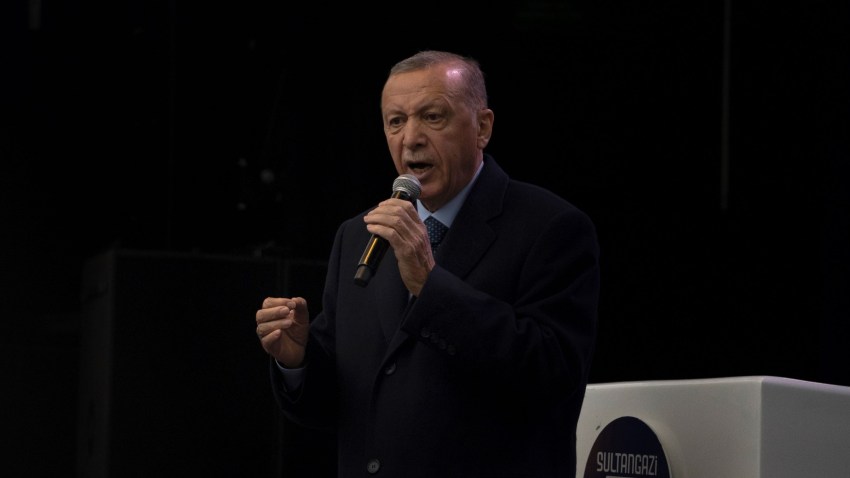

Since his sweeping overhaul of Turkey’s political system in 2017, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has cemented his near-total control over the country, even if he has undermined the country’s democracy to do so. Under his increasingly authoritarian rule, dissent has become more and more dangerous, with numerous opposition leaders, civil society figures and journalists having been arrested on what most observers consider to be politically motivated charges.

Last year, however, the combination of a tail-spinning economy, a disastrous emergency response to the February 2023 earthquakes and a united political opposition seemed to present Erdogan with his greatest electoral challenge in his 20 years in power. He ended up winning May’s presidential election handily, and his coalition government maintained control of parliament. But recent municipal elections, in which his ruling Justice and Development party suffered stinging losses, suggest that Erdogan’s era of dominance could be coming to a close.

For the past decade, Erdogan has also pursued an adventurous and bellicose foreign policy across the Mediterranean region, putting Ankara increasingly at odds with its NATO allies. After Turkey’s purchase of a Russian air-defense system in July 2019, Washington suspended Turkish involvement in the F-35 next-generation fighter plane program. Turkey’s repeated incursions into waters in the Eastern Mediterranean claimed by Cyprus, as well as its standoffs with Greek and French naval vessels in the region, further raised tensions and alarmed observers. And Ankara’s support for political Islamists since the Arab uprisings as well as its role in the Middle East’s various armed conflicts have put it at odds with the Gulf states and Egypt.

With U.S. President Joe Biden having restored a more conventional approach to U.S. foreign policy and alliance management, and amid a shift in the Middle East toward diplomatic engagement, Erdogan has more recently sought to smooth relations with Turkey’s allies and neighbors. The Russian invasion of Ukraine seemed to add urgency to that effort, but that hasn’t stopped Erdogan from playing a game of brinksmanship to gain concessions from Sweden in return for unblocking its membership applications to NATO. And none of the underlying causes of tension between Turkey and the U.S. and Europe have been resolved so far, meaning that a return to confrontation cannot be ruled out, especially if it ever serves Erdogan’s domestic political interests.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s involvement in Syria’s civil war increased Ankara’s leverage there, but at times pitted Erdogan against Russian President Vladimir Putin in the military and diplomatic competition to shape the end game of that conflict. Its involvement in the Libyan civil war on behalf of the United Nations-recognized Government of National Accord similarly put Turkey at odds with both Russia, which supports the forces of Gen. Khalifa Haftar, and Ankara’s European partners, which had sought to enforce an arms embargo on the country. Most recently, Turkey’s political and military support for Azerbaijan in its 2020 war with Armenia over the breakaway Nagorno-Karabakh region once again put it at the heart of a conflict with direct implications for Russia’s national security interests. Nevertheless, Erdogan has managed to maintain open channels of communication with Putin that he has tried to leverage into a mediating role in the war in Ukraine, at times with some success, as with the Black Sea Grain Initiative.

Since his reelection last year, Erdogan has signaled yet another foreign policy reset, adopting a more conciliatory posture toward Turkey’s NATO allies and European partners. But as always with Erdogan, today’s thaw can easily transform into tomorrow’s confrontation, depending on his political needs of the moment.

WPR has covered Turkey in detail and continues to examine key questions about what will happen next. What are the prospects for Turkey’s political opposition and civil society as Erdogan enters his third decade in power? Will Turkey choose engagement or confrontation when it comes to regional diplomacy, particularly over the conflicts in Syria and Libya? How lasting will Erdogan’s conciliatory approach to ties with the West end up being? Below are some of the highlights of WPR’s coverage.

Our Most Recent Coverage

A Weakened Erdogan Is Still Bad News for Turkey’s Democracy

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s political position is weaker than it has been in nearly a decade. That spells trouble for Turkey’s democracy.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in July 2019 and is regularly updated.