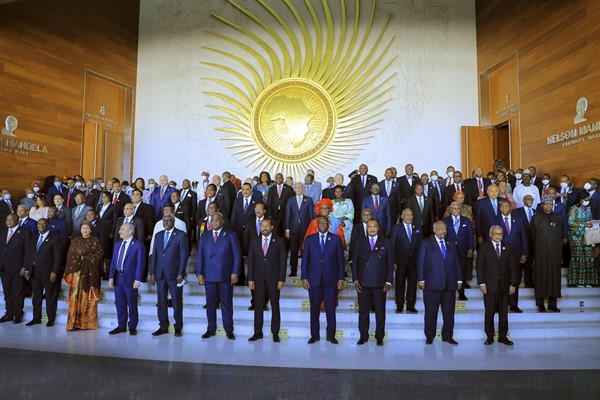

Last week, 13 African heads of state and government attended the African Union’s Mid-Year Coordination Meeting, the principal forum for the AU and Africa’s Regional Economic Communities, or RECs, to align their priorities and coordinate implementation of the continental integration agenda. This year’s meeting, the fourth since the format was launched in 2017 to replace a mid-year leaders’ summit, was focused on issues like the status of regional integration in Africa; the division of labor between the AU, its member states and RECs; a tripartite free trade agreement between the East African Community, The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa and the Southern African Development Community; an interregional knowledge-exchange platform on early warning and conflict prevention; Africa’s response to the coronavirus pandemic; and the impact of the Ukraine crisis on the continent.

The gathering took place in Lusaka, Zambia, which had not hosted a continental meeting since 2001. It also came a little over a week after the AU commemorated the 20th anniversary of its founding on July 9. Debates about the AU’s role in Africa’s affairs and its effectiveness at grappling with the issues facing the continent have raged over the past decade, and they have intensified in recent years amid multiple challenges to peace, security and governance across Africa.

The AU can certainly be proud of several achievements since its creation in 2002, following the dissolution of its predecessor organization, the Organization of African Unity. To begin with, Africa—and its approximately 1.4 billion people—now sits at the center of global affairs, notwithstanding the unequal distribution of power in the international system, and the AU has played a part in putting it there. As noted by Emmanuel Balogun, an assistant professor of political science at Skidmore College in New York,

the AU is a key actor in global politics and has served as Africa’s voice in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine crisis. The AU’s member states form the single largest regional group at the United Nations, and, given their tendency to vote as a bloc on major issues, their support is regarded by the U.N. Security Council’s five permanent members to be of considerable importance.

The creation of other key AU instruments, like the African Union Peer Review Mechanism and the Peace and Security Council, has helped bolster the union’s institutional capacity to seek transparency and accountability from its member governments. As a result, Africa’s international partners regularly look to the AU to take the lead on important issues affecting the continent and its people. Prominent among these is trade. After many years of negotiation, The African Continental Free Trade Area, or AfCFTA, launched on Jan. 1, 2021, to much fanfare. It is expected to

boost intra-African trade by about $35 billion by end of 2022. In the long term, the market area will likely attract investment for the continent’s infrastructural, industrialization and commercial aspirations, which should create jobs, reduce poverty and lead to prosperity for Africans.

From the onset of the coronavirus pandemic,

the AU won praise for taking a multilateral approach to fighting the virus, working with Africa’s regional organizations, pan-continental bodies like the African Export-Import Bank and private sector actors to assist African governments with contact-tracing, distribution of PPE supplies and vaccine acquisition. And while those efforts were stymied in large part by

vaccine nationalism on the part of wealthier, industrialized countries in the Global North, the timely intervention of the AU undoubtedly saved millions of lives.

But the AU’s shortcomings are also substantial, and I have written extensively for WPR about some of them. Many Africans regard the bloc as little more than an ineffective “dictators’ club” that is unable to provide constructive solutions to difficult problems across the continent, in large part because it is in thrall to its member governments. In conflicts and crises across Africa, from Cameroon and Mali to Ethiopia and Sudan, the AU is typically slow to respond—and when it does, its interventions are often found wanting. As I wrote in an article last year,

many of the AU’s shortcomings are structural in nature, but as the organization tasked with creating common positions for the continent on key global issues, it is fair and reasonable for Africans to expect—and even demand—better from the bloc.

The AU’s role in mediating conflict within and between member states remains among its primary weaknesses, despite several institutional reforms implemented over the years to enhance its ability to do so. The lack of consistency in its responses is a notable problem.

For instance,

Mali, Guinea, Sudan and Burkina Faso are currently suspended from AU activities for recent military coups overthrowing elected civilian leaders, while Chad—where the army effected an unconstitutional change of government following the death of longtime ruler Idriss Deby—was spared such treatment. Similarly, governments and leaders accused of human rights abuses, graft or violating constitutional term limits also remain in good standing within the AU, which many observers argue is not only hypocritical, but weakens the AU’s credibility and its ability to respond to graver challenges when they emerge.

In fairness to the AU, as well as to its institutional leadership and the continent’s leaders,

they are increasingly taking note of these critiques. Two recent AU summits,

which aimed at tackling Africa’s humanitarian and political crises, reckoned with the many gaps between the bloc’s rhetoric and its actual behavior. And there is broad agreement that the AU must further reposition itself on these issues as Africa’s role in global affairs grows in prominence and importance.

That effort must begin with the AU resolving its longstanding funding problems, as it cannot continue to rely on donations from foreign partners if it truly desires to be autonomous and

deliver on its ambitious Agenda 2063. The continent’s leaders continue to push for a permanent African presence in international fora like the U.N. and the G-20, with Senegalese President Macky Sall—the AU’s current rotating chairperson—writing

a recent op-ed calling for the AU to be admitted into the latter body.

Those calls are worthwhile, but if the AU is to play a more constructive role as Africa’s voice in the next 20 years, they must also be backed by meaningful efforts within the AU to ensure that its own norms and rules are consistently adhered to by its member states.

Keep up to date on Africa news with our daily curated Africa news wire.

Civil Society Watch

Nearly a year after the government of Uganda suspended 54 NGOs for alleged improprieties, the chilling effect that crackdown has had on civil society organizations in the country is palpable. Many Ugandan civil society groups, working on a range of issues from the environment and election monitoring to women’s rights, have been

targeted because of their public opposition to government policies or the support they provided to opposition figures as well as activists and even ordinary citizens.

President Yoweri Museveni has accused the targeted NGOs of being agents of foreign governments seeking to undermine the Ugandan government by replicating—if not replacing—the role of state institutions. But many observers believe the clampdown is simply an effort to suppress organizations believed to be challenging Museveni’s policies and undermining his rule.

Culture Watch

Uganda’s inaugural pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, or the Venice Biennale, has been recognized with a Special Mention award. The two Ugandan artists featured in the pavilion—Collin Sekajugo, a painter, and Acaye Kerunen, a weaver—were honored for “their vision, ambition and commitment to art and working in their country” during the awards ceremony on the biennale’s opening day. The eight-month exhibition includes 213 artists from 58 countries, including several that, like Uganda, are participating for the first time, including Cameroon and Namibia.

Chris O. Ogunmodede is an associate editor with World Politics Review. His coverage of African politics, international relations and security has appeared in War on The Rocks, Mail & Guardian, The Republic, Africa is a Country and other publications. Follow him on Twitter at @Illustrious_Cee.