Of the 380 million eligible voters in the 28 countries of the European Union, very few will actually bother to cast ballots in the May 22-25 European parliamentary elections, according to recent polls. Popular disinterest in these elections runs deep, and the trend toward massive abstention—already 60 percent in the most recent EU elections in 2009—will likely be the polls’ biggest winner. Facilitated by the present climate of crisis, right-wing parties, which number approximately 60 across Europe, continue to surge for their part, raising concerns about their weight in the next parliament. What exactly are their chances of success?

Analysts do not all agree that the far right

will obtain a significant number of the European Parliament’s 751 seats. Yet it is clear that Euroskeptic populist and nationalist parties have gained momentum over the past few months and succeeded in imposing their preferred themes on the debate. Some of these parties have also experienced a meteoric rise in recent years, including historic gains made by Marine Le Pen’s National Front (FN)

since France’s 2012 presidential election. If the upcoming elections confirm such trends, it will not be without consequences for the European political project, which far-right forces aim to curb.

Among the favorite themes of the far right are, of course, Europe’s still fragile economic situation, rising unemployment across the continent, incompetent and corrupt elites and a standard of living those parties claim is eroded by globalization and the euro, which Euroskeptics more generally believe to be behind all of Europe’s ills. The emphasis, however, is more specifically laid on two other anxieties that seem to resonate in the hearts and minds of many Europeans: a feared loss of identity and culture, due to the EU’s erosion of national sovereignty and its opening of EU member states to “foreign invasion.” As such, free movement within the visa-free Schengen area, the EU’s enlargement eastward, cooperation with countries to the south,

immigration and “Islamization” are all seen as having opened the gates to “enemies” in Europe’s midst.

Undoubtedly, the European far right has successfully capitalized on Europe’s socioeconomic turmoil, a decline in popular confidence in existing institutions as well as in traditional political parties of both left and right, the EU’s perceived incoherence and a wider rightward shift in public opinion that has legitimized the far right’s anti-system rhetoric. The far right’s members have more specifically been able to strengthen their position by resorting to a simplistic and Manichaean ideological discourse that, sadly, has been more audible and catchier than that of their competitors.

In particular, the far right’s monopolization of the electoral debate is all the more pronounced as a number of traditional parties, worried that their electorates might defect, have chosen to reclaim many of the themes embraced by right-wing currents. The rightist Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) in France, for example, does not propose to exit the Schengen area, but does suggest reforming it and limiting immigration. Such political appropriation of far-right themes is not new by itself, but the need for traditionally pro-European parties to re-legitimize the European project and reaffirm it as a guarantor of peace in Europe is. The fact of the matter is that Europe no longer inspires younger generations as it did a few decades ago, except in the east, where concerns about Ukrainian instability and Russian ambitions have inspired calls for renewed intra-European solidarity.

Should one, therefore, expect a historic result for the far right and the emergence of a cohesive group in the European Parliament able to influence European decision-making? It appears highly likely that populist and nationalist parties will get more deputies in the current elections than they did in 2009. The FN is already set to win nearly 25 percent of the French vote, ahead of both the UMP and the Socialist Party, which would mean between 15 and 20 representatives for the FN, compared to only three at present. Similar results in other countries could facilitate the emergence of a united political front that would allow European right-wing forces to develop a robust identity within the European Parliament and thereby draw substantial benefits, like funding, offices, the right to table amendments to pending legislation and access to parliamentary committees. But this process will be more complex and arduous than expected for several reasons.

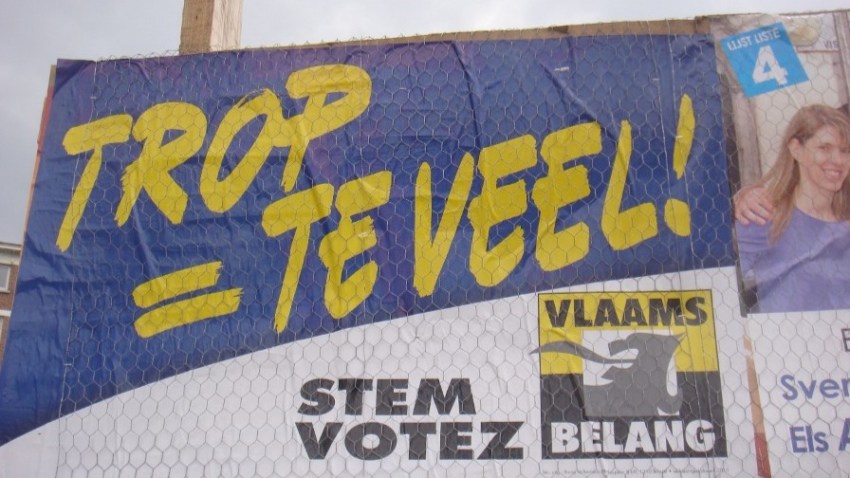

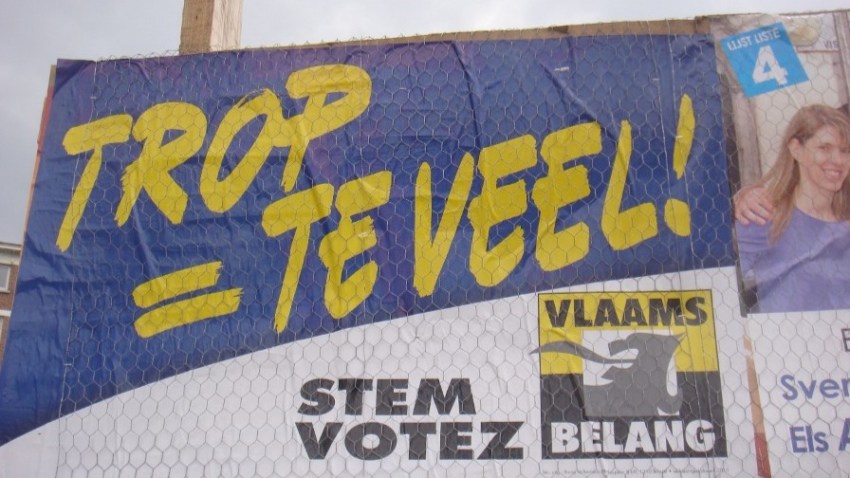

Beyond a common anti-European, xenophobic and Islamophobic discourse, right-wing parties in Europe are divided by considerable ideological differences and are in open competition. The European Alliance for Freedom headed by Le Pen and bringing together seven parties—the FN; the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom of Geert Wilders, who compared the Koran to Hitler’s “Mein Kampf”; Belgium’s Vlaams Belang; Austria’s Freedom Party; Italy’s Northern League; Slovakia’s National Party and the Sweden Democrats—opposes another movement of the same type, the Alliance of European National Movements, which assembles even more-extremist parties with which the FN officially wants no link. However, the FN was itself rejected by Nigel Farage’s right-wing and Euroskeptic United Kingdom Independence Party for having “anti-Semitism in its DNA.”

Given all of this, the real question going into these elections is not how well right-wing parties will do, but rather whether they will be able, once the results are known, to assemble a broader audience of Euroskeptics, and what impact their discourse about Europe will have on European citizens’ support for the European project. Depending on the answer, this could be the greatest challenge, in the longer term, facing Europe and its political survival.

Myriam Benraad is a specialist on Iraq at Sciences Po-Paris (CERI) and a policy fellow at the Middle East and North Africa Program of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).