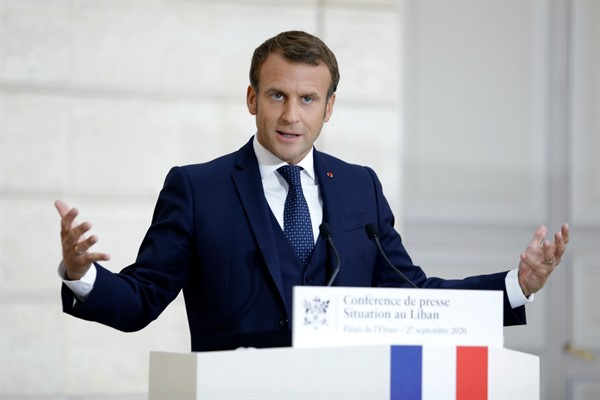

It’s been a busy few months for Emmanuel Macron. The French president has taken the lead in seeking to resolve a range of crises and conflicts within Europe and on its borders and periphery. That has put Macron where he clearly likes to be: center stage and in the spotlight. But in so doing, he has once again created opposition and resentment within Europe, while underlining the limits to his ability to achieve his desired outcomes.

Macron’s diplomatic hot streak began at the European Union summit in late July, when he helped push through the EU’s groundbreaking collective debt mechanism to fund pandemic relief packages. Then, in early August, he flew to Lebanon to publicly pressure its leaders to implement long-needed reforms in the immediate aftermath of the Beirut port explosion. He subsequently engaged in a very public war of words with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan over Ankara’s brinksmanship in the Eastern Mediterranean. And this week, he visited Lithuania and Estonia, both EU and NATO members, as part of a trip meant to assuage their misgivings over his recent outreach to Russia.

The guiding logic of Macron’s diplomacy is consistent with the longstanding view among the French foreign policy establishment that Europe should become a more autonomous strategic actor in what is seen in Paris as an increasingly multipolar world. This explains Macron’s emphasis on strengthening the EU’s institutions, particularly when it comes to fiscal redistribution and security cooperation. The EU pandemic relief fund was the latest—and most significant—in a series of incremental advances he has achieved since taking office in 2017. This vision of what Macron calls European “strategic autonomy” also explains his insistence that the EU should vocally and forcefully stand alongside Greece and Cyprus in their territorial disputes with Turkey, even at the risk of military confrontation. The idea that the EU must become a strategic actor has made inroads in Brussels, to the point that European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called hers a “geopolitical commission” when she took office in December.