PORT AU PRINCE, Haiti — Wealth appears to be directly related to the altitude of your housing in Port au Prince: The higher you live the richer you are. The headquarters of the U.N. stabilization force, MINUSTAH, is midway up the mountain. Most of the U.N. workers appear to live in Petionville, as high up as you can get. Traveling higher, the roads improve, the cars get nicer, and traffic-choked streets give way to tree-lined avenues and gated estates.

MINUSTAH headquarters is located in the old Hotel Christopher, and buzzes with activity as white “UN”-emblazoned Toyotas filled with administrators and blue-helmeted and heavily armed soldiers careen in and out of the compound. Haiti feels like a different country from this elevation.

I’ve spoken to dozens of people from various layers of Haitian society about MINUSTAH, and in spite of some grumbling about displays of wealth and occasional ignorance of Haitian customs and language, there seems to be wide agreement that the improvement of the security situation is due almost entirely to the U.N. presence. Haitians speak of last year’s wave of kidnappings and daily shootings as a dark period of their country’s history that is now in the past. They credit MINUSTAH for the security they are now experiencing.

The professionalizing of the Haitian National Police (HNP) is the U.N.’s hedge that security will remain once they leave.

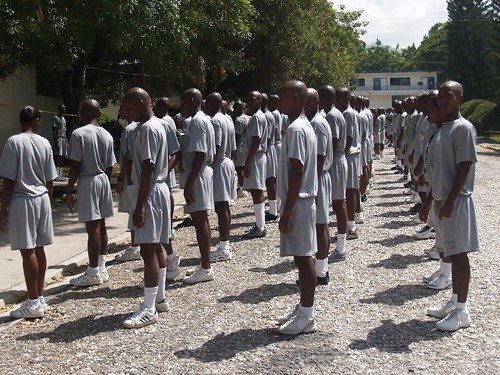

Fred Blaise is a police officer from Florida and is the spokesman for UNPOL, the 1,200-strong force of police officers from 36 countries deployed here to police the nation and help train HNP cadets. He drives me to the police academy to see the training in action. Over 600 new cadets graduate from the national police academy every six months, and the countrywide police force has grown to over 8,000. The goal is to train and equip 20,000. Do the math and you’ll realize the U.N. isn’t planning on completely leaving anytime soon. I’m not given access to the cadets, but I do manage to speak with Jean Miguelite Maxime, the inspector general of the academy. He speaks with passion about creating a sense of national identity in his trainees and, beyond stability, the need to strengthen Haitian society as a whole. This is a common theme I hear. The stability that the U.N. presence provides is essential. But unless Haiti’s lack of jobs and poor education system are addressed, Haiti could easily tip back into chaos again.

Haitian National Police trainees (Aaron Ernst)

The next interview I’ve arranged is with a journalist at Radio Soleil, and it’s too late for me to call a driver. So I take a tap-tap, the ubiquitous buses most Haitians use for transport. I am deposited in Belaire, a very poor part of town where people openly stare at the only white person in sight. Kids yell “Hey you!” and “Blan!” and hiss to get my attention. Diseased-looking dogs eat from massive mounds of garbage in the middle of the street. I ask a woman for directions and she asks me for 25 gourde (about $1) as payment. I give her 5 gourde and am immediately surrounded by a crowd of women and children grabbing my hand, pulling at my camera pack, and asking for money.

After my interview, I again stand on the street waiting for my driver to arrive. It’s getting dark and I’m aware of the thousands of dollars of video equipment in my backpack. When the driver finally shows up, I step back into the world of the haves, more aware than ever just how much Haiti’s future depends on how well it takes care of its have-nots.