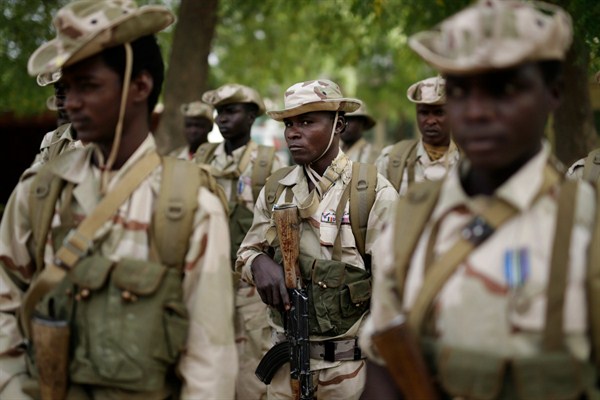

On the morning of May 5, Boko Haram militants attacked a Chadian military post in the Lake Chad region near the border with northeast Nigeria, where the extremist group is based. Nine soldiers were killed, the latest casualties suffered by Chad’s military as it responds to a crisis that, on Chadian territory alone, has left hundreds dead and displaced more than 100,000.

The following day, in the capital, N’Djamena, the Chadian Convention for the Defense of Human Rights reported that Maounde Decladore, one of its activists, had been arrested. Decladore is also a spokesman for the group “It Must Change,” which has denounced the policies of longtime Chadian President Idriss Deby. His arrest came in the context of a wider crackdown on Chad’s increasingly emboldened government critics—just two days, in fact, after two other activists with anti-government views, Nadjo Kaina and Bertrand Sollo, received six-month suspended sentences for attempted conspiracy and incitement.

These two events—the attack on the military post and Decladore’s arrest—might appear at first glance to be unrelated, but analysts say the link between them is unmistakable. In recent years, Chad has established itself as an essential security partner of Western powers eager to combat terror threats in West and Central Africa, chief among them Islamist extremists in northern Mali and Boko Haram. The deaths of nine soldiers point to the risks of this strategy. So far, though, the rewards for Chad and Deby appear to outweigh them. Along with rising diplomatic clout—including the selection in January of former Foreign Minister Moussa Faki Mahamat as head of the African Union Commission—Deby has been given an increasingly free hand to govern as he pleases, safe in the knowledge that France and the U.S. will likely keep quiet. As he navigates a severe economic downturn and rising anti-government sentiment, he is taking advantage of this freedom by employing draconian methods against domestic opponents.