Serap Çileli, activist and author, was born in 1966 in Mersin, Turkey. Her family emigrated to Germany when she was eight years old. When she was 12, her father engaged her to a man for the first time. Serap attempted suicide and got out of the impending marriage. At 15, she was no longer able to avoid being married to a stranger. She left school in Germany and moved to Turkey. After seven years, the marriage ended and Serap was able to convince her parents to let her return to Germany with her two children. As soon as she returned, however, her father began looking for another husband for her. Serap fled to a women’s shelter and slowly built her life with her current husband, Ali.

Çileli was one of the first German women of Turkish descent to write a book about her experiences. Now she travels around Germany advocating for Turkish women and helping girls who reach out to her.

Following are selected questions and answers from a speech given by Çileli at the DGB Haus on Nov. 22, 2006, and from an exclusive interview before the session. Comments made in the interview are interspersed with those from the speech, and the translation of some answers is paraphrased.

Tell me about your work as an activist against domestic violence, incest, forced marriage and honor killings.

I hold talks at conferences and seminars and am asked to testify at state parliaments around the country. I have counseled about 250 young people, including three boys. Most of the girls were between 14 and 21. It is my job to create awareness about the problem. I don’t want to promote stereotypes; I’m trying to develop sensibility toward the situation faced by many young women of Turkish origin in Germany.

What is the difference between an arranged and a forced marriage?

Many girls I work with say their marriages are arranged — i.e. they say they’re allowed to pick the man they want. Of course, there are arranged marriages and there are love marriages. There are also forced marriages . . .

Not all arranged marriages are forced marriages. For me, the question is how a young girl is brought up? Can she make decisions for herself? Is she allowed to make decisions for herself? Or was she brought up to obey?

I consider about half of Turkish arranged marriages to be forced.

Boys and young men are also affected by forced marriage, but they have more room to make their own decisions and more freedom when they are married. It’s common practice for a young man to keep his girlfriend even after marriage.

What types of parents force their daughters into marriage?

All kinds of parents force their daughter into marriage. I have even counseled girls whose parents are doctors and lawyers. The girls were free to make their own choices until puberty hit. Then this freedom ended abruptly.

What are the consequences for the children in these marriages?

We now know that a child can sense in the womb if it is wanted or not. When a child isn’t loved, it will have psychological problems. Many of the so-called import brides that are brought from Turkey to marry in Germany are completely isolated, and the kids — wanted or not — are the only people with whom the mother has contact. These women rarely speak German, and their husbands often forbid them from taking a class. This is intentional disintegration. The men are scared that they will no longer be able to control their wives.

Does forced marriage have anything to do with Islam?

Forced marriage is practiced in many cultures and religions. It’s not an Islamic phenomenon. I am looking at this problem in Turkish society because I’m Turkish. [Çileli has become a German citizen.]

I do not want anyone to leave this program tonight with the impression that I’m simplifying this problem or ignoring the social problems faced by Germans. I also don’t want people to think that all Turkish women who live in Germany are faced with violence. There are migrant women who live in intact families, who are treated equally with their brothers, who are allowed to get an education and who don’t face violence. These women make a big contribution to integration in Germany.

Based on my observations, unfortunately this group of women is a small group.

In many families, boys grow up as first class citizens and girls are second class citizens. Boys see their fathers hitting their mothers and learn to abuse their wives. Daughters are seen as a burden and as a possible source of social shame.

The Quran says that men and women should be virgins at the time of marriage, but most men are no longer virgins by 18. Most of these young men have sex with non-Muslim girls but then want to marry a Muslim and a virgin.

What is an honor killing and how many happen in Germany?

The concept of honor is attached to the physical purity of the woman, and that’s why only her blood can cleanse the shame her actions bring on a family.

The Bundeskriminalamt (The Federal Criminal Police Office of Germany) says 59 murders in the name of family honor have occurred in Germany from 1996-2005.

Who are the perpetrators of honor killings?

In many cases, women are also involved in the murder — either passively or actively. Women, too, are responsible for upholding the honor of the family. If a girl shames her family, she shames the women in the family, too.

Your book about your experience of being forced into marriage was published in 2002, and many similar books by other authors have followed. What has changed since your book first came out?

In the past, the term honor killing was not even known. I had to convince journalists to write about what was happening.

The increased media coverage has given many girls the courage to fight the system. And with a wider understanding of the problem, people are taking a closer look at each other, including their neighbors.

But I still ask myself why Turkish immigrants continue to have such conservative ways? There’s plenty of influence from the media via satellite TV, and nothing has happened on the Turkish side to help integration. Germany has no integration policy, and the country only recognized itself as an immigrant country two years ago. The first law to fight forced marriage was passed in 2005.

Preaching in the mosques also affects behavior. There are 3,000 mosques in Germany and 350 kindergartens run by [the Islamic association] Milli Görü, [which has strong links to Turkey]. These schools offer tutoring and language classes. These are all places of indoctrination, but Germans are afraid to admit this.

The first guest workers were uneducated and held fast to their traditions because they were afraid of a majority society with a different religion. The second generation, my generation, is the commuter generation (who lived a few years in Turkey and a few years in Germany), and we didn’t have the chance to really make Germany our home.

Now this second generation is marrying off the third generation mostly with relatives from Turkey. We’ve had 10 years of import brides — which brings us back to a community of first-generation immigrants. These girls are chosen because they’re raised in a traditional way and obedient, etc. These are the daughters that are preferred. These women are often isolated from society, don’t know German and are kept like slaves at home.

When girls come to you for help, what kind of problems do they face?

I worked with a girl named “Gülbahar” who is now 24. When she was about to be forced into marriage with a cousin, she told her mother that her father had abused her. Her mother’s reaction: This marriage is decided and you must be married as a virgin. Otherwise, your cousin or your father will kill you. Because of the threat of losing face, Gülbahar’s parents pronounced a death sentence for her. The girl’s father told one of his friends to kill her so his family honor could be restored. Gülbahar was able to run away. The mother could have helped the daughter, but the mother stood by the father. The parents gave Gülbahar one week to commit suicide or said she would be killed. The girl is now in therapy and is fighting anorexia. She will need help for many years and her father is walking the streets of Germany as a free man who never faced any consequences.

In another extreme case, a girl had a German boyfriend and didn’t want to marry the chosen cousin from Turkey. She was very emancipated and fought back, threatening to leave the family. When the mother found out about the daughter’s threat, she told her sons to rape her own daughter. This girl was raped the next day as punishment. She was then locked up, and I couldn’t reach her. At some point the girl’s German boyfriend came to me asking for help and support. And with the help of another family member, this girl was able to get out of the four-room apartment where the family lived. This case is an extreme case. But the mothers are often very involved in keeping up the family honor. One reason is the traditional way in which these women are raised. When I try to help girls, I often have to work hard to convince the mothers before we can take action against the father.

How often do you come across underage brides?

Germany is always very concerned about the rights of women in Afghanistan or Pakistan. But right here in Germany there are child brides who are being married against their will. The youngest married girl I have helped was 11.

These girls who are playing in the schoolyard at 12, 13 or 14 years are forced to live in a completely different world. Some are brought to husbands in their homelands. Others are married right here in Germany. They are children without a childhood who are raped from one day to the next. They lose all trust in other people and are isolated and abandoned. They are considered part-time wives and live under the watch of their parents-in-law. They are sent to school to live with their secret right here in our neighborhoods. The girl is delivered helplessly into the parental control and violence of her parents-in-law and husband. She has no chance to live out the dream that she dreamed together with other girls her age who were also born in Germany: to study or learn a trade, to become independent, to design her own life, to encounter love, to marry a man of her choice and to have children — all without any pressure.

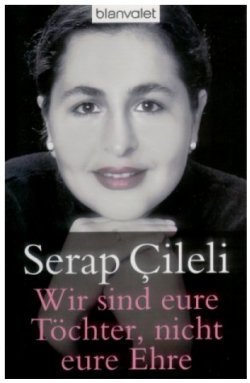

Serap Çileli’s book, “We Are Your Daughters, Not Your Honor,” was published in 2002 and is available in German. Her Web site is: www.cileli-serap.de