When former U.S. Marine Amir Mirzaei Hekmati was sentenced to death for espionage by an Iranian court earlier this month, he was accused, among other things, of helping to make video games. In his televised “confession,” Hekmati stated that, after working for the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, “I was recruited by Kuma Games Company, a computer games company which received money from [the] CIA to design and make special films and computer games to change the public opinion’s mindset in the Middle East.” He added, “The goal of Kuma Games was to convince the people of the world and Iraq that what the U.S. does in Iraq and other countries is good and acceptable.”

Needless to say, neither Hekmati’s alleged confession nor his conviction means the charges are true. Rather his arrest is better seen as yet another indicator of the escalating geopolitical tensions between Tehran and Washington. Still, the incident highlights the extent to which video games and international politics have increasingly intersected in recent years.

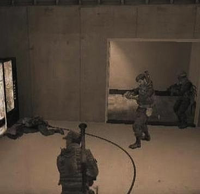

As with any other form of popular culture, digital video games can be bearers of incidental or intended political ideas. For instance, with military simulations and “tactical shooters” being the most popular genres, it is hardly surprising that the post-Sept. 11 era would spawn a variety of U.S.-produced games that involve some combination of terrorism, counterinsurgency, weapons of mass destruction, the Middle East and similar headline topics. Kuma Games, for example, offers more than 100 scenarios for its Kuma\War game series, most set in Iraq or Afghanistan. Three scenarios involve Iran: Two are based on the failed 1980 American hostage rescue mission, while a third, released in 2005, concerns a fictional U.S. raid on an Iranian nuclear facility. The same company also produces “Sibaq al-Fursan,” an Arabic-language car-racing game set in a radioactive, post-apocalyptic Persian Gulf, where the villains fly Iranian aircraft and drop North Korean bombs.