For more than six decades following India’s independence in 1947, urbanization remained an afterthought for policymakers, who hardly recognized the positive relationship between urban expansion and economic development. It wasn’t until 1984, when Rajiv Gandhi became India’s youngest prime minister and brought with him a new, young brigade of leaders, that those in power began to acknowledge that urbanization could serve India’s economy. Gandhi’s initiatives on urbanization, while new, were nonetheless hesitant.

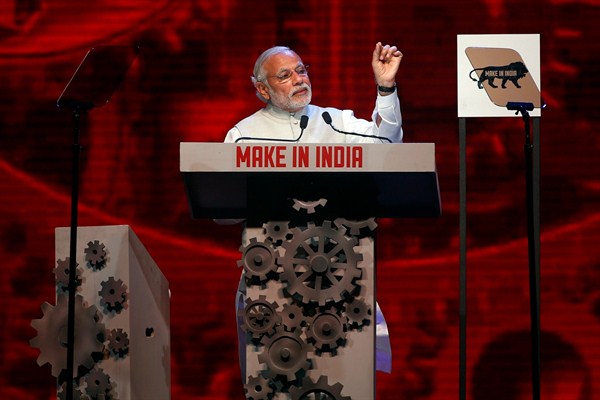

Through the 1990s and the early 2000s, analysts increasingly spoke of India’s “urban turn” and hinted at the beginnings of a serious investment in urban infrastructure and connectivity. But in practice, the government remained reluctant to enact policies that would support an urban future. That changed in May 2014, when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was elected. Within months, new Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Make in India initiative, encouraging multinational and domestic companies to manufacture products in India, signaling a major policy shift toward industrialization and urbanization.

However, it remains to be seen whether the BJP’s new approach is achievable, and what its likely consequences will be if it is implemented. These questions are important, but the answers are not obvious, as the Make in India initiative is constrained by two historical features of India’s economic development: low and slow urbanization and a small industrial sector. Official figures indicate that only 31 percent of India’s total population is urban. Moreover, the rate of urban expansion is slow—urban growth in India is lower than in almost all other developing regions, and below what its own urbanization rate was during the much-maligned slow-growth period from the 1960s through the 1980s. Some of the poorest regions in the eastern and northern parts of the country have barely urbanized. Furthermore, existing urban areas are often inhospitable to migrants, with high levels of poverty.