Recently published climate science ultimately underscores the same points: The impacts of climate change are advancing faster than experts had previously predicted, and they are increasingly irreversible. Despite these warnings, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest reports confirm that the world remains on pace to blow past the goal of restricting the rise in average temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, with likely catastrophic consequences.

Persistent climate skepticism from key global figures, motivated in part by national economic interests, is still slowing diplomatic efforts to systematically address the drivers of climate change. In 2022, the COP27 Climate Change Conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, raised questions about the relationship between climate justice and social justice, given Cairo’s human rights record, and resulted in disappointing outcomes in terms of new climate commitments. But the conference did produce a historic breakthrough when the wealthier, industrialized states of the Global North agreed to fund a “Loss and Damage” mechanism to help states of the Global South address the costs and impact of climate change that can no longer be reversed.

Last year’s COP28 also generated controversy for being hosted by the United Arab Emirates, a major fossil fuels exporter. While the conference’s final communiqué included a call for the world to shift away from fossil fuels for the first time, it failed to deliver significant concrete progress on other sticking points to climate action, including much-needed financing for countries that can’t afford the costs of the green energy transition.

The Paris Climate Agreement has nevertheless proved more resilient than many initially feared after the U.S. withdrew from it in 2017 under then-President Donald Trump. The European Union, Japan and South Korea all pledged to achieve carbon-neutral economies by 2050, and China announced a target of achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. In one of his first moves upon taking office in 2021, Trump’s successor, President Joe Biden, issued an executive order returning the U.S. to the Paris agreement, while later announcing that the U.S. would double its emissions reduction target to 50 percent by 2030. And congressional passage in August 2022 of a $370 billion climate bill to promote the transition to renewable energies marked the first such legislation in U.S. history.

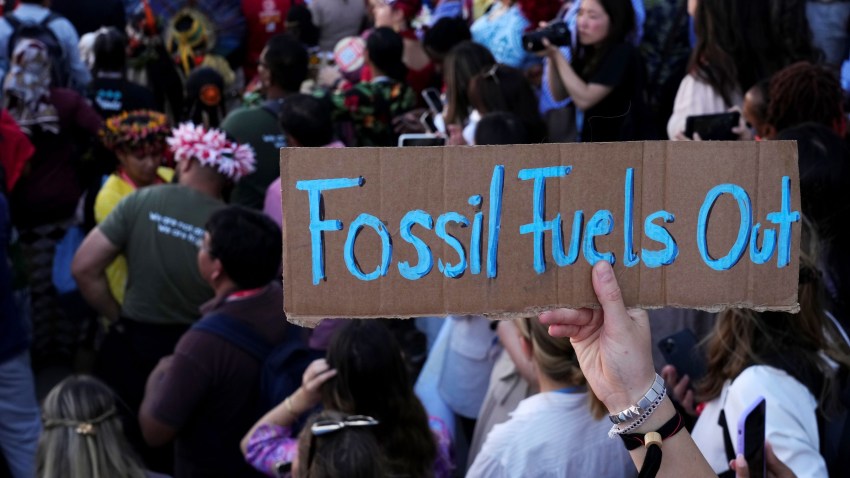

Whether renewed U.S. leadership on the issue will be enough to break through some of the obstacles facing climate diplomacy remains to be seen, as evidenced by the mixed bag of results that came out of the most recent summit in Dubai. And after making gains in elections across Europe in the late 2010s and early 2020s, Green parties have recently shed support due to a variety of factors—including popular backlashes to perceived imbalances in how the burden of climate action is distributed—dampening their electoral prospects as well as hopes for ambitious climate policy in general. In the meantime, frustration with the slow progress and persistent challenges toward achieving increasingly urgent targets has spurred newfound activism, particularly among young people, for whom addressing climate change is a question of intergenerational justice.

WPR has covered climate change in detail and continues to examine key questions about what will happen next. Will youth activism upend existing political orders and usher in new, climate-focused leaders? Will the Biden administration’s climate diplomacy and policies survive the November presidential election? And will the green transition become yet another arena for international competition, rather than cooperation? Below are some of the highlights of WPR’s coverage.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in June 2019 and is regularly updated.