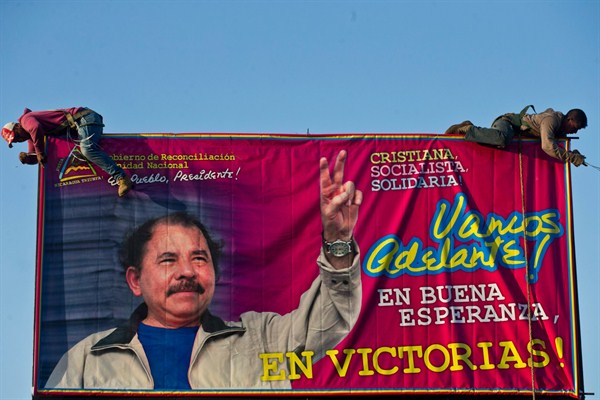

In November, Nicaraguans will head to the polls to elect a president, members of the National Assembly and representatives to the Central American Parliament. The elections will be the country’s first since constitutional reforms were passed in 2014. The likely victor of the presidential race, President Daniel Ortega, can now be elected with a simple plurality, although he is predicted to win more than 60 percent of the vote. It would be his fourth term since being elected in 1984 and his seventh presidential campaign overall. Though his candidacy comes as no surprise, two recent controversies—one international and one domestic—have revived debates about Ortega’s stewardship and the status of democracy in Nicaragua.

The first controversy involves the recent expulsions of six environmental activists and three U.S. officials, two of whom were reportedly conducting counterterrorism activities without government permission. The third U.S. official, a professor at the U.S. Army War College, was conducting research on the proposed and controversial interoceanic canal. The U.S. State Department, along with the Mexican government, responded to these expulsions by issuing a travel alert that included a warning of street protests and security concerns surrounding the upcoming elections.

The subtext of the alert, a tool reminiscent of the 1980s, was that the situation in Nicaragua is volatile and that the government is cracking down on dissent. Unlike some neighboring countries, political violence is actually quite rare in Nicaragua and scuffles with police often result in as many police being injured as civilians. While the U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua, Laura Dogu, has thus far maintained that Nicaragua’s upcoming elections are a matter for the Nicaraguan people, various U.S. officials are likely to criticize the electoral process and Ortega in the months to come. Neither the expulsions nor the response happened in a vacuum. While Nicaragua and the U.S. have been building a more constructive relationship in recent years, the history of U.S. intervention in the country casts a long shadow.