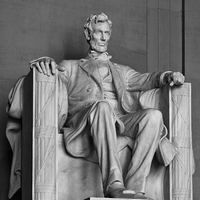

Watching a president dismiss a senior general inevitably calls to mind Abraham Lincoln, who during the Civil War sacked generals left and right until he found one who served his purposes, and Harry Truman, who famously fired Gen. Douglas Macarthur during the Korean War.

Unlike his predecessors, who removed generals either for their performance or due to disagreements over policy and strategy, President Barack Obama let Gen. Stanley McChrystal go because McChrystal had permitted a command environment that led some of his staff to crudely dismiss the president's advisers. As if to underscore the continuity in policy and strategy, Obama appointed Gen. David Petraeus as McChrystal's replacement. Petraeus, credited with turning the Iraq war around and generally having a better ear for politics, was instrumental in the 2009 policy review that produced the strategy that McChrystal was executing in Afghanistan.

The commentary on McChrystal's removal has focused on civil-military relations and the domestic political implications for Obama's national security image. Obama's defenders, who range across the domestic political spectrum, cite Lincoln and Truman and the principle of civilian control of the military. But those who focus on McChrystal's impolitic comments as justification for his departure risk missing the larger point -- namely, the contradictions and fecklessness of a policy that created the frustration on the ground to begin with, and which led some members of McChrystal's staff to vent their feelings to a Rolling Stone reporter.