The Libya intervention has capped a difficult decade for airpower. While the combination of airstrikes and special forces units on the ground quickly overthrew the Taliban regime in 2001, the utility of airpower in counterinsurgency was called into question over the course of the long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. It was hoped that the intervention in Libya would restore airpower's luster by quickly defeating a tyrant bent on destroying his political enemies. But the campaign launched by the West's most powerful air forces has thus far failed to dislodge Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, or even to force him to yield very much of the country to rebel rule.

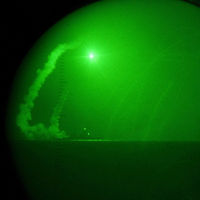

Nevertheless, airpower -- including such offshore strike capabilities as submarine-launched cruise missiles -- remains attractive to civilian policymakers. Air operations carry less risk of military casualties than ground operations, making them more palatable to domestic audiences. Airstrikes also grant civilian policymakers the illusion of control, as precision munitions have given rise to the notion that strikes can be launched against specific, discrete military targets without serious danger of destroying civilian facilities like orphanages, hospitals and other sensitive sites that risk turning public opinion against the intervention. That airpower rarely keeps its promises is beside the point. Few civilian policymakers study military affairs closely, relying instead on military advice, and air force generals and other airpower advocates offer cheaper solutions than "boots on the ground" zealots.

To this list of airpower's attractions we may now have to add legal impunity. In order to avoid the restrictions of the War Powers Resolution, the Obama administration has determined that operations against Libya do not constitute "hostilities" under the definition required by law. Although the argument is legally complicated, the administration is essentially claiming that because the conflict involves minimal to no threat of harm to U.S. military personnel, it is not a "war" in the sense envisioned by the War Powers Resolution. While the legal formulation is tailored to Libya, where continued direct U.S. participation is marginal, the logic of the argument could apply to a wide range of interventions involving warfare conducted from sea- or air-based platforms. Effectively, if the target can't shoot back, it ain't war.