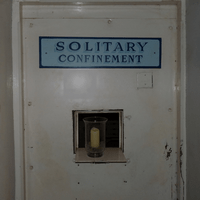

In July, a group of prisoners in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) of California’s Pelican Bay State Prison went on a hunger strike to protest their conditions of confinement.

Central to the prisoners’ complaints was the fact that for years and, in some cases, for decades, they have been held in prolonged and indeterminate solitary confinement with few privileges and opportunities to engage in productive programming and activities. Importantly, as one prisoner put it in a letter to the informational website Solitary Watch, they were asking for “human justice, . . . fairness, compassion, positive reform, dignity . . . to bring awareness about what’s going on here in the SHU, the torture and suffering.”

These demands are not only perfectly reasonable; they are also for the most part legally required. The right to be treated with respect for one’s human dignity is one of the most basic of human rights. It is guaranteed in numerous international human rights instruments, which also stipulate that, other than the limitations inherent in the deprivation of liberty -- such as on the freedom of movement -- prisoners retain their human rights and freedoms while incarcerated. Furthermore, an absolute prohibition against all forms of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment and punishment is reaffirmed in a large number of human rights instruments, including two international treaties -- the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the United Nations Convention Against Torture (CAT) -- that are legally binding on all signatory parties to them. This prohibition is also enshrined in the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits cruel or unusual punishment.