The list of of nations with nuclear weapons continues to grow. First it was the United States and the Soviet Union. They were soon followed by the United Kingdom, France then China. Later, India, Israel, Pakistan and North Korea joined. South Africa was a member of the club for a while, before abandoning its program. Iran will become a nuclear power some day, even if the United States or Israel postpones it a bit with an attack. A growing number of other states could build nuclear weapons in short order if they wanted to, including South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Brazil and many of the European states. Al-Qaida wants nuclear weapons and may some day get them. And it is not inconceivable that another violent apocalyptic organization will try to steal or buy them, or that a powerful criminal gang with money and connections will consider nuclear weapons the ultimate tool of extortion and self-defense.

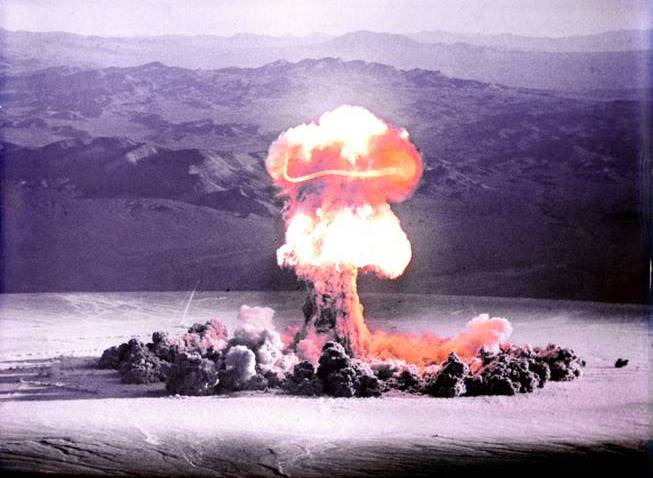

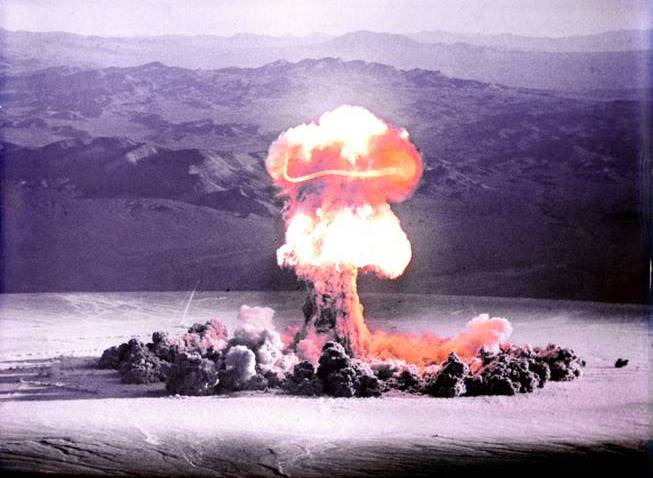

Logic suggests that the more nuclear powers there are, the higher the possibility that nuclear weapons will be used -- whether out of desperation by a crumbling or unstable regime or pure wickedness by terrorists or criminals. If this happens it is possible that the U.S. military will be ordered to help stabilize a shattered nation and provide humanitarian relief; to secure any remaining nuclear weapons; to control important facilities; or to help the victim of the nuclear attack repel an invasion. Despite these possibilities, today's U.S. armed forces are unprepared to operate in an environment contaminated by a nuclear explosion.

It wasn't always this way. During the Cold War, U.S. policymakers expected that a full-scale war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact would go nuclear. Soviet doctrine made clear that Moscow planned to use nuclear weapons; the United States did not rule out its own nuclear strikes in response to a Soviet nuclear attack or impending conventional defeat. Because of this, the U.S. military was prepared to function after a nuclear attack or exchange. Units were equipped and trained for it. Combat formations were assigned nuclear decontamination units. In a sense, these efforts were a charade. Anyone who served in the military at that time knows the preparation would have been woefully inadequate in the face of a major nuclear exchange. But it was something. It is often better to be ill-prepared than unprepared.

Today the U.S. military is, in fact, unprepared to function after a nuclear attack or exchange. It does plan to help civil authorities prevent nuclear terrorism and assist if an attack does occur. It is prepared to interdict the movement of nuclear weapons. Many Department of Defense wargames and planning exercises

focus on securing nuclear weapons following the collapse of a nuclear armed state. But there is very little in the way of military doctrine, concepts, equipment, training, war-gaming or capacity-building for operations following a nuclear attack or exchange in a foreign country.

Despite this, it is easy to imagine ways that a nuclear scenario could unfold. The psychotically paranoid North Korean regime could exhaust its last small supply of sanity and lash out against South Korea, Japan or the United States. Or other nations might be forced to use nuclear weapons to pre-empt an imminent nuclear attack from Pyongyang. A nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan is imaginable if, for instance, Islamabad felt it was about to lose a conventional war or if Pakistani nuclear weapons were to fall into the hands of extremists who use them against India. Any potential conflict between nuclear-armed China and India remains dangerous. Miscalculation by Israel or a nuclear-armed Iran is possible, as is the escalation of a conflict between a nuclear Iran and a nuclear Saudi Arabia. It is not hard to imagine that Taiwan would pursue nuclear weapons and use them against a Chinese invasion. Russia, which relies on its massive nuclear arsenal to compensate for shortcomings in its conventional forces, could feel threatened enough to strike. Several of the current and most-likely future nuclear states could collapse into civil war, with one or both sides in control of nuclear weapons and desperate to stave off defeat. And this doesn't even consider the emergence of unexpected new nuclear states, nuclear-armed terrorists, criminals or some new violent apocalyptic group like Aum Shinriko.

Should any of these nightmares unfold and the United States feels compelled to intervene, simply staying alive in a contaminated, apocalyptic wasteland would be a challenge for U.S. troops. The simplest functions would be extraordinarily difficult, not only for frontline units but also for those trying to resupply or reinforce them or to evacuate casualties. The local infrastructure, information grids, medical care and government services would be destroyed or overwhelmed. Moving and communicating would be hard or impossible. American units would be surrounded by civilians who were, at best, badly shocked and unable to find food, water and medical care and at worst suffering from radiation burns and poisoning. All would be begging U.S. troops for aid, and the American public would probably demand that it be delivered. U.S. military commanders on the ground would have to decide whether to do so at the risk of failing at their assigned missions, thus creating intense ethical dilemmas that would challenge unit cohesion and morale. American troops are not psychologically equipped to ignore the pleas of dying civilians, particularly when some of them would likely be fellow Americans. And if one nuclear weapon were already used, there would be a chance of a second or third one as well, thus putting intense pressure on the American military commander who would be well-aware of the danger his or her troops faced.

The pure horror of such scenarios suggests that the U.S. military should devote time and resources to preparing for them. But in this period of long-term austerity in defense spending, the military clearly cannot prepare for everything. Policymakers and military leaders are forced to accept increased risk in some areas and on some functions in order to focus their preparation on others. That is simply the way strategy works. The question is whether the spread of nuclear weapons is making post-nuclear operations the wrong place to accept risk.

The highest priorities in U.S. military strategy today are homeland defense, disrupting and destroying transnational terrorist networks, air defense and control, protecting the global commons such as sea lanes and cyberspace, building partner capacity, and expeditionary operations after overcoming sophisticated anti-access defenses. It is hard to argue that any of these are unimportant and should get fewer of the increasingly scare defense resources.

But in today's world, being able to function in a nuclear environment is just as crucial. While the American military cannot fully prepare for this -- doing so may not even be possible -- it is important that it start thinking about the problem, beginning with analysis and war games. Then, when cuts in the defense budget at least slow at some point in the future, there will be an intellectual foundation for this most tragic yet necessary military capability. The U.S. will be more secure for the effort.

Steven Metz is a defense analyst and the author of "Iraq and the Evolution of American Strategy." His weekly WPR column, Strategic Horizons, appears every Wednesday.