Edward Snowden, the former National Security Agency contractor who turned over a trove of information about U.S. surveillance programs to the media and foreign government agencies, continues to dominate the news. His story, like that of U.S. Army Pvt. Bradley Manning, is a complex tangle of important issues involving the privacy rights of Americans during the conflict with transnational terrorism; the process by which the U.S. government decides what information is classified and what is open; and the building of a massive national security bureaucracy that necessarily gives low-level, inexperienced people the power to do great damage to programs they do not understand.

But Snowden's association with WikiLeaks and his flight to avoid American authorities, which has so far taken him to China and Russia, indicate that another, even bigger issue is also at play: the ability of America's opponents to exploit concerns about transparency and openness against the United States as part of a broad, integrated, asymmetric containment strategy.

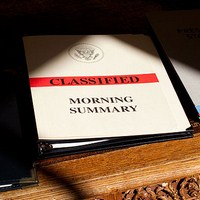

This vulnerability comes from deep within American strategic culture and history. The United States was born out of an instinctive mistrust of government. Always watchful for the abuse of power by the government, Americans traditionally demanded to know everything their government was doing. One result of this was the institutionalization of personal privacy rights.