With its economy in trouble from a high public debt burden as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, Zambia’s government recently suspended interest payments on some sovereign bonds. The country is already in arrears on some of its debt—including $183 million in official bilateral loans from other countries and $256 million from commercial banks—and has asked for a six-month suspension on interest payments from the holders of its $3 billion in Eurobonds, which are denominated in foreign currencies. These bondholders are due to make a final decision on Zambia’s request in mid-November, but a substantial portion of them have so far indicated an unwillingness to provide such a payment holiday.

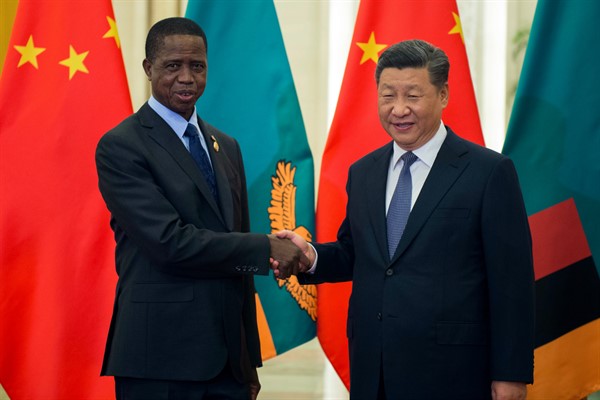

While Zambia has been portrayed as the first pandemic-related default, the country’s debt burden was significant prior to the arrival of COVID-19. Zambia’s borrowing surged over the past decade, with loans from bilateral creditors—especially China—for infrastructure projects, and from private bond markets for general consumption. Zambia’s 10-year Eurobond issue in 2012 carried an interest rate of around 5.6 percent, a relatively low rate for a “frontier market” country. But its debt burden increased dramatically in subsequent years, and by mid-2019, the Eurobonds issued in 2012 were trading at a yield of 20 percent, suggesting dramatically higher borrowing costs if Zambia sought new credit. In August 2019, a joint International Monetary Fund-World Bank debt sustainability analysis warned that Zambia was in a perilous position: Interest payments on its debt had become quite substantial, analogous to charges on a high-interest rate credit card.

In the years after the global financial crisis, creditors became more willing to lend to governments from low- and middle-income countries. In a global environment with persistently low interest rates, emerging and frontier markets offered private investors opportunities for higher returns. And, for creditor countries, especially China, loans represented a pathway to new trade and investment opportunities, as well as to expanded soft power and diplomatic influence. Between 2008 and 2020, the public debt of low- and middle-income countries more than tripled.