In discussing my proposal last week for a Sino-Indian Convention that would define 21st century spheres of influence in Central Asia, a colleague suggested that it was an idea that Otto von Bismarck would have been proud of. They didn't mean it as a compliment.

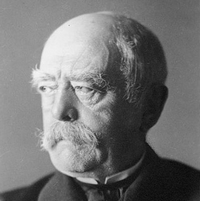

We think of Bismarck as a caricature of the old European warlord, peering through a monocled eye while croaking about decisions forged in "blood and iron." Most of all, we see him as someone whose policies were designed for personal and imperial aggrandizement, not the betterment of the people. We distrust his approach to the world because it seems unsavory -- built on deals conducted in back rooms with no regard to the popular will.

Bismarck might appeal to autocrats who treat policy like a game of chess, but he is never cited as someone relevant to U.S. decision-makers. The democratic policymaker, we are told, must craft policies that pass the approval of higher standards: fidelity to values and a commitment to improving the plight of the common citizen. We cannot play a "Great Game" in the center of Asia, because we don't approve of treating policy like a competitive sport.