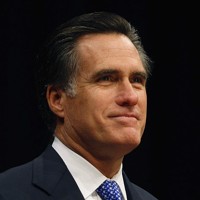

Mitt Romney’s recently described Russia as the “No. 1 geopolitical foe” of the United States, arguing that Moscow consistently “lines up” with America’s adversaries. But does the claim stand up to closer scrutiny? After all, Moscow has not extended material and financial support to the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan, arguably the greatest challenges to the United States, even though there are ample geopolitical justifications to try and bog Washington down in multiple Middle Eastern quagmires, thereby deflecting American attention from Eurasia. Nor does Russia reflexively block any and all U.S. priorities, as the Soviet Union routinely did during the days of the Cold War.

Nonetheless, Russia does not see eye to eye with the United States on every issue, with Syria being exhibit No. 1. It also does not fully support the American position on Iran: Moscow has been reluctant to impose draconian sanctions on Tehran, even if it has cooperated with more limited measures, including canceling the sale of a major air-defense system to Tehran that, if it were deployed, would make any U.S. or Israeli air strike against Iran's nuclear facilities much more problematic. Indeed, Moscow has itself adopted the rhetoric of “selected partnership” to characterize its relations with the United States. It believes it can have an energy partnership with America, highlighted by Exxon-Mobil’s alliance with state-owned Rosneft to develop new offshore fields in the Arctic, and it actively supports the transit of U.S. troops and materiel into Afghanistan. Yet Moscow does not feel obligated to support every last U.S. foreign policy preference and feels that it can oppose the United States on some issues without having to jeopardize those areas where productive relations have been created.

But Russia’s position -- supportive of the U.S. on some issues, in active opposition on others -- does not fit well into America’s historically binary foreign policy approach, by which other states are classed as either “friends” or “foes.” An outgrowth of the Cold War era, reinforced during the War on Terror, the attitude that countries are either “with us,” and thereby expected to more or less line up with every U.S. position, or “against us,” and therefore classified as adversaries, is hard to shake.