Peacekeeping is a tragic business. That may seem obvious, if only because, when reading about United Nations peacekeeping operations, you come across the word "tragedy" a lot. It describes what happened in Bosnia and Rwanda all too neatly. There's no better word for what took place in Haiti, where more than 100 U.N. personnel were among the 250,000 dead in January's earthquake.

But, as English professors have tried to explain to generations of dozy students, "tragic" is more than just a synonym for "awful." Great tragedies -- Oedipus Rex, Macbeth, Scarface -- aren't just about suffering. They center on protagonists who, in trying to shape the future, make choices that lead to disastrous consequences. There's a long tradition of political theorists who adopt a tragic vision of international affairs in which, in the words of Chris Brown of the London School of Economics, "there are no unambiguously right answers" to foreign policy problems. In practice, that means that, "To act is, necessarily, to do wrong."

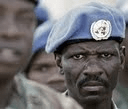

That could stand as a pretty accurate summary of the choices that U.N. officials and their masters in the Security Council face in places like Darfur and the Democratic Republic of Congo, currently the U.N.'s two biggest missions. Over the last decade, the Security Council has mandated a series of increasingly ambitious peace operations. The U.N. now commands just more than 100,000 troops and police worldwide. Yet as its operational reach has grown, it has found itself trapped in situations in which it has been forced to sacrifice principles for the sake of political pragmatism, and to support a range of undemocratic and unpleasant regimes.