When the finance ministers of the G-20 nations met on the sidelines of the annual IMF-World Bank meetings in Washington last weekend, it marked the sixth time they had convened since the fall of 2008. When the G-20 leaders meet this summer in Toronto, the total number of summits held since the global financial crisis erupted will hit double digits.

And yet, despite early cooperation that addressed the global liquidity shortfall, little substantial progress has been made in the area of international financial regulation. Given the trauma that the entire world economy has suffered, in part due to a lack of such regulation, one would think more headway would have been made by now. A closer look, however, reveals a litany of factors that has created conditions making coordination points incredibly difficult to locate and even trickier to maintain.

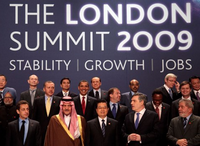

The G-20 summit in London last April focused squarely on addressing sticky global credit markets still reeling from subprime fallout. Members responded by patching together a $1.1 trillion liquidity package that, among other things, tripled the resources of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). By the time of the Pittsburgh summit that September, the focus had shifted from stemming the crisis to preventing a sequel through coordinating national financial regulatory policies across the group's membership. So, since Pittsburgh, what have the major proposals been and what progress has been made toward reaching agreement?