As the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th Party Congress unfolded last week, culminating in Xi Jinping’s appointment to a third term as party leader on Sunday, observers around the world tried to discern how Xi’s concentration of power in Beijing might affect security and stability in the Indo-Pacific region. In particular, with tensions flaring since U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei in August, fears have grown that Xi might seek to cement his political legacy by ordering an invasion to seize Taiwan. In this context, every reference Xi made at the gathering to Taiwan’s status was analyzed in minute detail for their potential implications by analysts in the U.S., Japan, India and Australia.

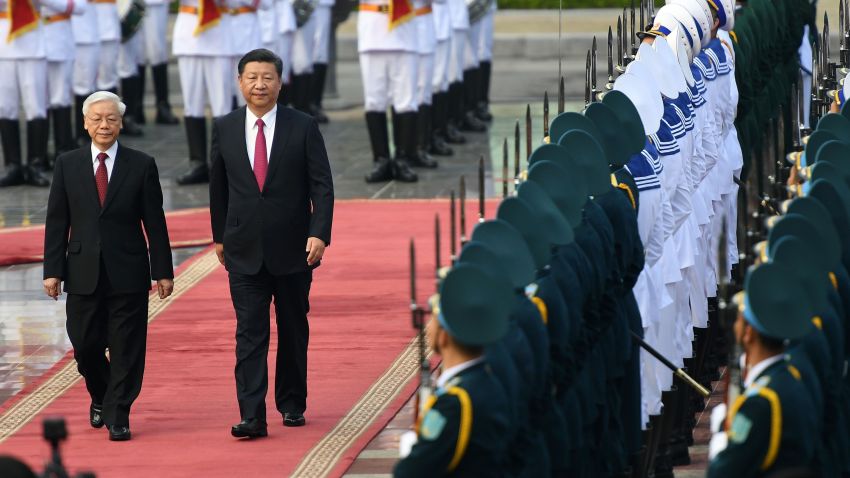

Yet while these states facing fraught trade and security disputes with Beijing have managed to build a strategic cooperation structure through the so-called Quad framework, known formally as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, the state in the Indo-Pacific region facing the most difficult security dilemmas with regard to a more aggressive China under Xi is Vietnam. Even as Nguyen Phu Trong, the Vietnamese Communist Party’s general-secretary, prepares to become the first international leader to travel to Beijing to meet with Xi following his third-term investiture, Hanoi is struggling to manage the adverse effects of a deterioration in bilateral relations that began when Xi first took power a decade ago.

Starting with Beijing’s island-building program in the South China Sea that has turned atolls that are the subject of territorial disputes into major Chinese military bases, sources of conflict between Hanoi and Beijing have proliferated since 2012. By 2019, angry disputes over oil drilling and fishing rights in the South China Sea’s disputed waters had escalated to the point where Vietnamese and Chinese coast guard ships regularly rammed each other in efforts by both sides to signal their unyielding determination to stick to their territorial claims. Shaped by historical narratives of centuries of resistance to foreign invaders—including a succession of Chinese emperors—Vietnamese public opinion has at times openly vented frustration with Chinese demands, despite risks of police repression in what is still an authoritarian system controlled by the ruling Communist Party.